Performance art: expression set in motion

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 1976, to accompany her exhibition Stage Sets, the American artist Joan Jonas wrote: “performances did occur might occur/but the rituals are yours/here among the temporary icons/we [ . . .] a garden/where, touching you with an image/we left you.”

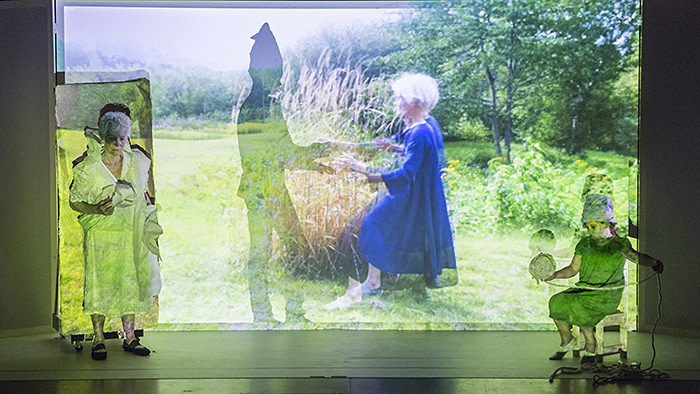

Trust Jonas, always as poetic with her words as her images, to sum up the impermanent allure of performance art. Jonas made her first performance, “Oud Lau”, in 1968 (it was later filmed as “Wind”). Depicting a cluster of people battling to walk into gale-force winds on an icy, deserted shoreline, its depiction of human vulnerability in the face of climactic forces feels if anything more relevant today than when it was made.

Today, Jonas is a colossus of contemporary art. Her international status was assured in 2015 when she was chosen to represent the US at the Venice Biennale; this year’s major survey at London’s Tate Modern capped the honours. Performance art, meanwhile, is a vital strand in our visual tapestry. This week alone sees performer and choreographer Alex Baczynski-Jenkins take the Frieze Artist’s Award, while Kemang Wa Lehulere has a solo show at Marian Goodman gallery.

It wasn’t always so. The roots of performance art may well go back to pre-historic times. Who knows what rites those cave painters enacted in the firelight? Back then of course the gap between art and life was so narrow as to be often invisible. Where does religious rite end and imaginative spectacle begin? The performative aspect of spiritual ritual is so familiar to us as to go unremarked.

Even without the metaphysical element, the one-off happening has been popular in manifold epochs. The duties of Raphael’s father, Giovanni Santi, as court painter to the Duke of Urbino in the 15th century included staging theatrical events. Two hundred years later Bernini, best known for his gravity-defying sculptures, devised scenarios that included “L’Inondazione”, a recreation of the flooding of the Tiber.

The 20th century saw artists turn performative acts into a key component of their multi-faceted oeuvres. These practitioners included Dadaists and Constructivists; and then in the 1960s the odd rogue wolf like Yves Klein whose “Anthropometry” paintings were the imprints of naked female models who had covered themselves in Klein’s signature blue pigment while he conducted their movements, as if they were a cross between musical instruments and paintbrushes.

It was from the 1950s that performance started to become an art sufficient unto itself. In her study Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present (1979), RoseLee Goldberg pinpoints “18 Happenings in 6 Parts”, Allan Kaprow’s live 1959 “happening” (a term he invented) at the Reuben Gallery in New York as one of the first moments a public audience had a full experience of this transient form.

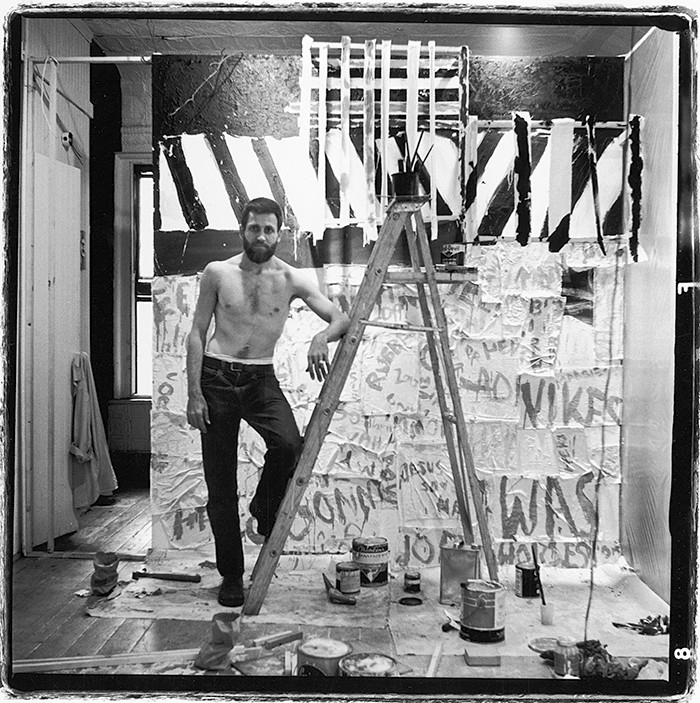

Kaprow studied with John Cage, the composer whose theatrical collaborations with choreographer Merce Cunningham and artist Robert Rauschenberg would crucially nourish later generations. Kaprow was also an action painter à la Jackson Pollock. According to Catherine Wood, senior curator of international art (performance) at Tate Modern, an essay by Kaprow entitled “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock” was critical for the evolution of the genre out of an era marked by the macho heroics of Abstract Expressionism.

“Kaprow makes the point that the photographs of Jackson Pollock were [for performance artists] more important than the paintings because they show the choreography and the dance on the canvas,” explains Wood.

Pollock is generally regarded as the All-American bad boy of Abstract Expressionism. Yet performance art was embraced by a burgeoning wave of feminist artists such as Jonas and Carolee Schneemann, both of whom were members of cross-disciplinary collective the Judson Dance Theater. Based in Greenwich Village and born out of Merce Cunningham’s teachings, the collective’s influence on the performance scene cannot be overestimated.

Jonas has said that performance gave women a chance “because it wasn’t male-dominated, as other forms were.” But there was more to its appeal. After centuries in which women’s bodies existed in art primarily to serve the male gaze, here was an opportunity for corporeal authorship.

Today, few raise an eyebrow when women paint, sculpt, photograph or film themselves. But when Yoko Ono, who emerged out of Japan’s autonomous tradition of performance art, invited an audience to snip away her clothes in “Cut Piece” (1964), such gestures of female authority were radically novel. Little wonder it travelled the world and became an icon of the genre.

Women artists also used performance actively to speak back to their misogynist oppressors. No feminist could watch Ana Mendieta dipping her arms in animal blood, as she did in “Body Tracks” (1982), then dragging them down paper to leave a ragged sinister imprint, without dancing an inner jig of delight at the snub to Klein’s plainly misogynistic “Anthropometries”.

The potential for political expression resonated beyond female ears. “[At the beginning] it was anti-institutional, anti-market and anti-status,” observes Wood. It is no surprise that a natural showman and self-proclaimed anarchist such as Joseph Beuys excelled at memorable happenings — for instance, his “I Like America and America Likes Me” (1974), in which he locked himself in a cage with a live coyote for three days.

It’s debatable whether the raft of performers who have chosen to live so dangerously have achieved much beyond their own fame and fortune. Maestra of masochistic melodrama is Marina Abramović. In 1974, her piece “Rhythm 0” saw her finish with a loaded gun held to her head by an audience member. “What I learnt was that . . . if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you,” Abramović said afterwards.

Yet how well she has survived. Today not only is Abramović a household name but she boasts Lady Gaga among her numerous disciples. But how much of her success rests, as Wood says, on her ability to “grasp the history [of performance art] and connect it to 20th-century spectacle and [onwards to] selfie-culture?”

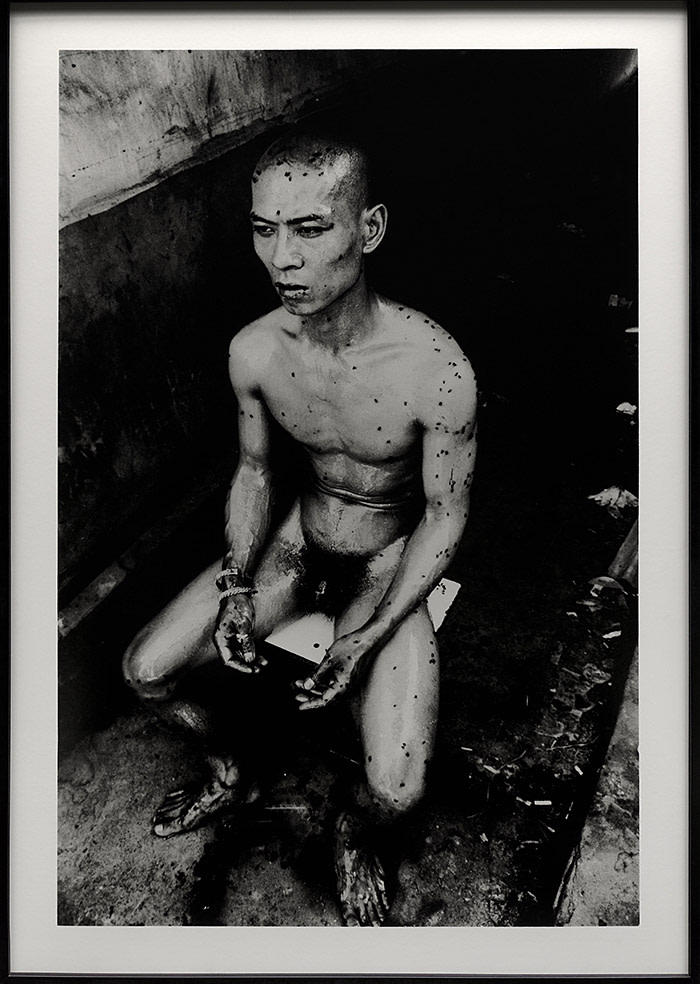

Nevertheless performance’s political relevance lives on, not least in repressive regimes where its ephemeral nature can make it a marginally less risky, yet still effective, form of expression than painting, sculpture or film. In China, the crackdown which followed the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 heralded an era of brutally unforgettable performance works. Zhang Huan, for example, was critically feted for the misery he endured when making “12 Square Meters” (1994), which saw him spend an hour covered in flies in one of Beijing’s filthy public toilets.

Meanwhile today in Bangladesh, a country struggling with issues of free expression, performance is thriving. At the recent Asian Art Biennale in Dhaka, a vibrant programme was led by performance artist Mahbubur Rahman, whose work focuses on colonisation and partition. Speaking to a local newspaper, Rahman said that performance was still a relatively new medium in Bangladesh but that it had “great potential”.

Increasingly we are aware that the abundance of imagery today dilutes its power to move us. No wonder it can be a performance — occasionally even eluding digital capture — that remains most vital in our interior archive.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments