Why the food at Carsten Höller’s new restaurant tastes Brutal

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

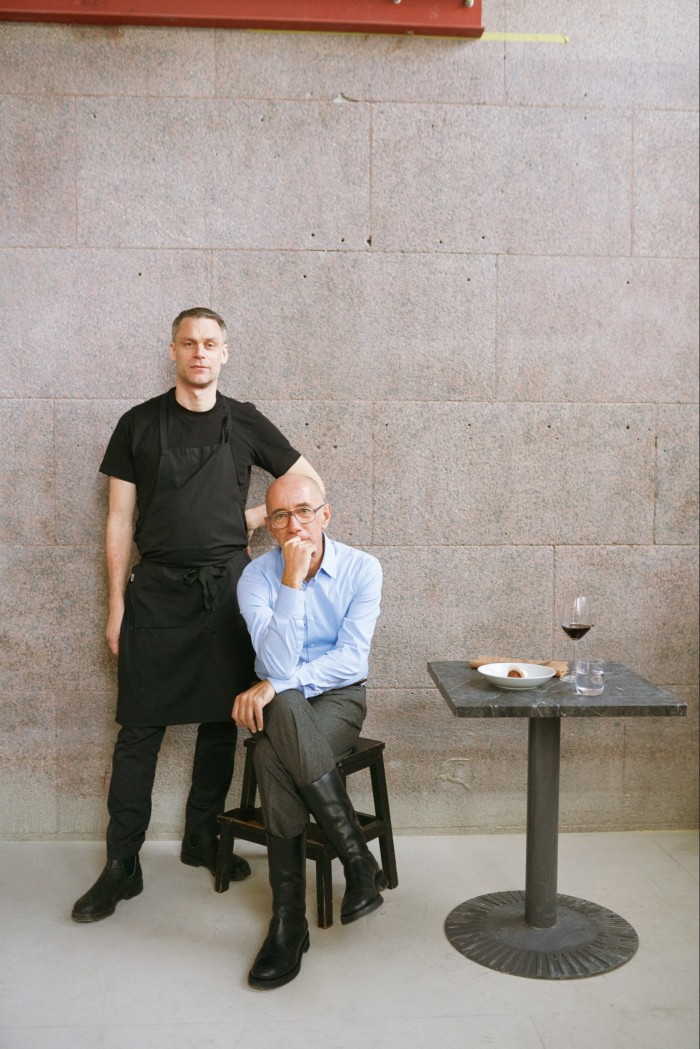

Belgian artist Carsten Höller – once dubbed the “Willy Wonka of contemporary art” – is best known for experiential works like the helter-skelter slides he installed at Tate Modern in 2006 or the Upside Down Mushroom Room that featured in his Fondazione Prada show in 2000. Branching out from art, he is about to open a restaurant near his apartment in Stockholm called Brutalisten, which will adhere to the principles of his “Brutalist Kitchen Manifesto”. I’ve come to Stockholm for a preview.

As the restaurant kitchen is yet to be finished, we meet for lunch at Höller’s apartment in central Norrmalm, which sits in a historic building opposite St John’s Church. When Höller moved in, there was no kitchen. He has since installed a stainless-steel cooking station; Brutalisten creative head chef Stefan Eriksson and his team are busy blowtorching produce when I arrive. Despite the plentiful art and books on display, the defining feature of the space is Höller’s collection of 35 rare songbirds, which he keeps in cages around the apartment. You walk into a room to the sound of wings flapping, like something out of Hitchcock’s The Birds. Trilling is also a constant. On one counter, I spot a tub of small wriggling worms.

The Brutalist Kitchen Manifesto, which Höller scribbled down one morning in 2018, consists of 10 precepts. These include “Don’t think recipe, it’s all about ingredients – go shopping or collecting and see what you find” and “Fancy decoration on the plate is avoided”. The gist, in keeping with the pared-back tenets of brutalist architecture, is that every dish should derive from just one ingredient and bring out its essential flavours via cooking methods that can be simple (“raw or quickly heated food” is ideal) or more sophisticated, so long as the aim is “purity”. Combining ingredients is verboten. A chicken dish, for example, can only make use of parts of the chicken, including the feathers, eggs, bones and meat, although the eggs needn’t come from the same bird. This is a “grey zone” – one of Höller’s several arbitrary distinctions. Salt is also allowed.

Höller gets around these infringements by using a sliding scale of classification. “Semi-Brutalism allows a minimum amount of ingredients but no spices. Like pasta with pike roe or cloudberry risotto,” he says. “Brutalism allows only water and salt. And ultra-orthodox Brutalism allows neither salt nor water. A raw oyster would be ultra-orthodox because you don’t do anything to it.” The menu will label its dishes accordingly. The point isn’t to be dogmatic so much as to spotlight each ingredient. Höller isn’t a stickler for the rules.

Höller is clearly into the provocation and play of the idea too. His “punchline”, as he puts it, is that we start off as brutalist eaters by feeding on our mothers’ milk. He also gets excited unpacking the possibilities, whether thinking up brutalist drinks made from apples, mushrooms or fish (“Think about cola from colatura,” he says of the Italian anchovy extract) or planning the restaurant WC facilities (could he dispense with loo roll altogether by installing a Japanese toilet?).

The idea of the Brutalist Kitchen sprang largely from Höller’s own style of cooking. An avid foodie, he eschews recipes and sources impeccable produce, which he cooks simply. The Swedish habit of smothering food in mayonnaise drives him crazy. Don’t get him started on the use of garnishes. At restaurants, he grumbles, “I get annoyed that chefs put too many things together because they think that’s what cooking is about. It kills the taste of the ingredient.” But does it matter if the end result tastes good? “Often it doesn’t taste as good as it would if the chef restrained [himself],” he replies. “Even at Noma, they can’t refrain from putting a flower on dishes. It’s not just flowers. It can be music. Many things. Sometimes you don’t want to be disturbed.”

Over lunch, I try six dishes, starting with a bowl of mussels from Bohuslän in west Sweden, which are smooth, slightly smoky, spare and deprived of their usual garlic and cream. To follow is a plate of broccoli, where different parts of the vegetable have been fermented, steamed, grilled and dusted with toasted broccoli seeds. “I’m sure people will say it tastes very broccoli-ish,” says Höller, neatly summing up the play of sweet, grassy, bitter flavours. Next comes a boiled and partly grilled langoustine, which is so heady and concentrated I can’t help craving mayonnaise as a relief and counterpoint. Knowing his views on the matter, I keep such considerations to myself.

A chestnut mushroom dish, where the fungus has been variously steamed, smoked, fermented or kept raw, recalls a deep, textured cream of mushroom soup. The guinea fowl, which includes grilled heart and breast, confit leg with its claw attached and an egg, liver, meat and skin mousse, is everything you’d want from a succulent cooked bird. But it’s the cod dish that really gets to me. Consisting of grilled chin, poached back and a sauce made from the head of Norwegian skrei cod – a fish known for its strong flavour – it is so saltily intense I feel giddy, even emotional, with each bite.

The other revelation is the venue. Rather than an austere concreted space, the 24-cover dining room (with 10 covers in the bar area) promises to be surprisingly vibrant, with pink neon signage, art by Dan Flavin and Congolese painter Moke, and a ceiling mural by artist Ana Benaroya, which Höller describes as “lots of big naked women, drinking and smoking like crazy”. How does that fit with the brutalist scheme? “The painting emphasises fun,” Höller says. “After all, this should be a place people come to enjoy themselves.”

Comments