The inside story of the Pfizer vaccine: ‘a once-in-an-epoch windfall’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Albert Bourla has become the world’s most in-demand chief executive. As vaccines permitted some countries to reopen their economies over the summer, the Pfizer boss flew into Cornwall for the G7 summit in June, parking his private jet next to Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s plane.

Weeks later, he was welcomed to the Olympics by then Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga, the first time officials could recall the Akasaka Palace state guesthouse hosting a corporate leader. In September, US president Joe Biden was describing the 59-year-old Greek-born “Albert” as his “good friend”.

The spectacular effectiveness of Pfizer’s Covid-19 shot has given the company the key to saving lives and economies. The World Health Organization estimates as many as half a million more people would have died this year in Europe alone if there had been no Covid vaccines.

By email, text or phone, global leaders have pleaded with Bourla for orders, in some cases hoping that it might rescue political careers. Facing an election battle he eventually lost, former Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu topped the list, calling Bourla 30 times.

But while western politicians rubbed shoulders with Bourla, leaders in many poorer countries were becoming exasperated, as the virus ripped through their unvaccinated populations. Strive Masiyiwa, the Zimbabwean billionaire who coordinates the African Union’s vaccine team, says they were “left treading water . . . until we were drowning”.

Late last year, he persuaded Pfizer to supply an initial 2m doses to help vaccinate some of the estimated 5m healthcare workers in Africa. He eagerly awaited a draft contract.

“They kept saying: next week. Then we got to April,” he says. In May, he watched as the EU struck a huge contract for up to 1.8bn doses. Infuriated, Masiyiwa wrote a “very heavily worded protest” to Bourla in which he asked what was causing the delay. They eventually received some doses from an initiative run by the Biden administration.

The pandemic has ushered in a massive expansion in the power of the state — from the war-footing in economic policy to forcing people to stay in their own homes. But when it has come to medical solutions to the pandemic, governments have been almost completely dependent on private companies.

The vaccine has transformed Pfizer’s political influence. In July 2018, Bourla’s predecessor was forced to abandon price hikes after being publicly shamed on Twitter by former US president Donald Trump. For years, its most famous product was Viagra for erectile dysfunction.

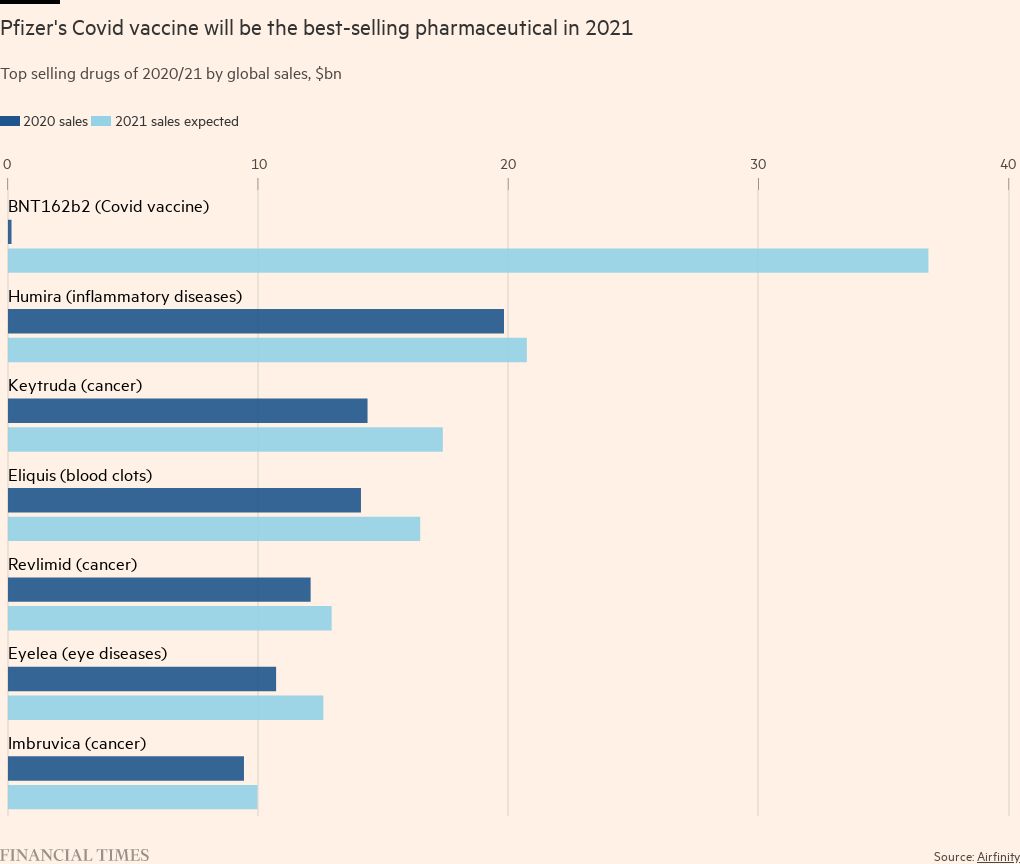

Now, the US drugmaker is behind the pharmaceutical product with the record for sales in a single year. Pfizer forecasts sales of the vaccine will hit $36bn in 2021, at least double those of its closest rival Moderna. Pfizer’s ability to dramatically expand production has made it by far the most dominant vaccine maker. In October, Pfizer had 80 per cent market share for Covid vaccines in the EU and 74 per cent in the US.

Since the vaccine’s approval at the end of last year, Pfizer’s decisions have helped shape the course of the pandemic. It has the power to set prices and to choose which country comes first in an opaque queueing system, including for the booster programmes that rich countries are now scrambling to accelerate.

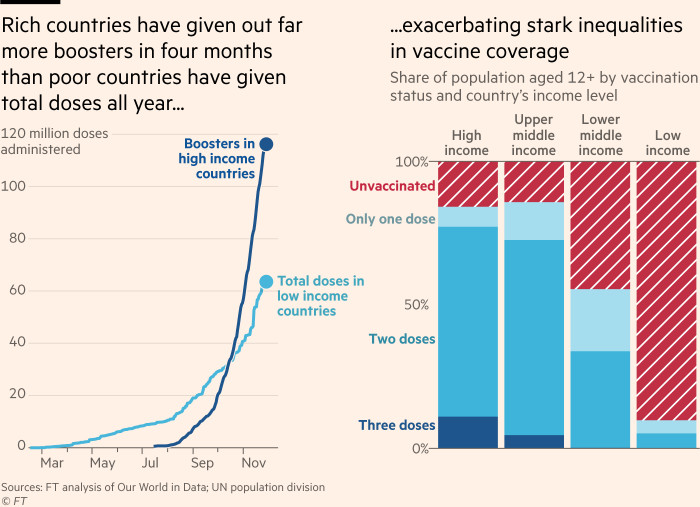

Depending on its decisions, countries, regions and even whole continents can open up their economies or risk falling behind in the race to control the virus. Although supplies of vaccines to poorer countries have ramped up since September, the global disparities are stark. So far, 66 per cent of people living in G7 countries have had two vaccine doses; in Africa, only 6 per cent. The number of people in high income countries who have had booster shots is almost double the number in low income countries who have received first and second doses.

The danger of such an unequal rollout has been underlined by the emergence of the new and potentially dangerous Omicron variant. Although its origins are still unclear, scientists have long warned that new variants are more likely if large parts of the world remain unvaccinated. “No one is safe until everyone is safe,” says Seth Berkley, chief executive of Gavi, the UN-backed vaccines alliance.

How Pfizer wields this newfound power — and what it plans to do next — is treated as top secret, as the vaccine maker blacks out large chunks of contracts and binds even independent scientists with non-disclosure agreements.

No Pfizer executive agreed to be interviewed for this story. Instead, the company responded through a spokesperson who said Pfizer is “immensely proud” of its accomplishment. “With more than 2bn doses delivered to date, our vaccine has saved millions of lives worldwide,” the spokesperson said.

The Financial Times has spoken to more than 60 people involved in the vaccine process, including current and former Pfizer employees and government officials across the globe, to lift the veil on how the company that has contributed so much to saving the world from Covid has also ensured it is such a lucrative business. They are all grateful for a safe and effective vaccine. But many question if the balance of power has tipped too far in Pfizer’s favour.

Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown University, says Pfizer and other vaccine makers have been “hard edged” in negotiations because politicians have been reluctant to push back.

“I’m not anti-Big Pharma . . . I think they have created a miracle, a scientific triumph,” he says. “But to say that they are wielding their power fairly, openly, with a sense of compassion, is manifestly untrue.”

The biggest marketing coup in history

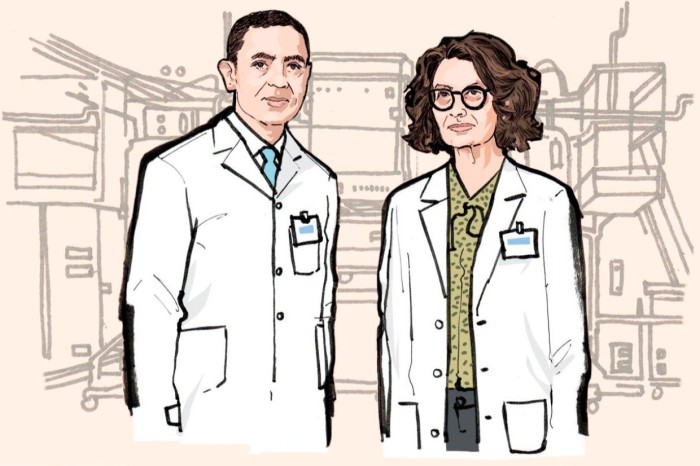

The vaccine Bourla has been fielding phone calls from world leaders about was actually invented in the labs of BioNTech, a pioneering company from the medieval German town of Mainz on the Rhine river.

In late January 2020, BioNTech’s chief executive Ugur Sahin watched the novel coronavirus emerging in China. Worried it would cause global havoc, Sahin, a Turkish immigrant to Germany who was an early believer in mRNA technology, marshalled BioNTech’s resources to invest in discovering a vaccine.

But, like Moderna, BioNTech had no approved products — and so no sales or profits. He had to search for a partner who had the dollars he needed.

His first stop was Pfizer because they had already worked together. The first time Sahin floated the idea of investing in his vaccine, the Pfizer executives initially hesitated. But in March, as the pandemic hit hospital wards around Pfizer’s Manhattan headquarters, the two companies announced a collaboration.

“It’s not even their vaccine,” as one former US government official involved in vaccine procurement puts it. The fact that it is now known universally as the Pfizer shot is “the biggest marketing coup in the history of American pharmaceuticals”.

Unlike AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer never considered selling its Covid-19 shot without making a profit. BioNTech needed to make money from its first product to plough back into the business. BioNTech would pocket half the profits but Pfizer controlled commercialising the vaccine in every country except the founders’ home territories of Germany and Turkey, and China, where BioNTech had already signed a deal with Fosun Pharma.

While BioNTech took up to €375m funding from the German government for development of the vaccine, Pfizer rejected US government money so it could keep complete control of the vaccine, including the crucial issue of pricing.

So when Pfizer opened negotiations with the US government in early summer 2020, it took an uncompromising stance: the company demanded $100 a dose — $200 a course — according to people familiar with the matter.

Bourla was “amazingly hands on”, according to one former Trump administration official, and unusually “personally involved” with discussions with people up and down the government, including at the regulator and the White House.

Moncef Slaoui had been appointed by the administration to secure vaccines. A GSK veteran, he was hardly hostile to the industry and knew the risks of vaccine development. But even he was shocked that Pfizer asked for such a steep price. Emotions ran high in the negotiations and Slaoui says he warned Bourla that the company would look like it was trying to benefit from a “once-in-a-century pandemic”.

One government official involved in the negotiations accused Pfizer of “trying to play hardball during a time of national emergency”. “How could we possibly have a soft spot in our hearts for Pfizer?” the official asks.

Pfizer did not respond to questions about its US pricing strategy. But a former Pfizer executive, present at the time, describes discussing the tricky art of pricing a vaccine during a pandemic. He points out that Pfizer’s pneumonia vaccine Prevnar, costs around $200. If the company used the costs of caring for Covid patients, or the benefits of reopening the economy to justify its pricing, then the bill could have been even higher.

“If you did a quick and dirty comparison versus Prevnar, it would be ridiculously high,” he says. “If you took into account economic impact, not just health impact, you could have it ranging up to $1,000 a dose, as there was the potential to avoid trillions of dollars in spending. You come back and think, ‘That’s not going to work’.”

Slaoui says Bourla soon recognised that such a price would risk Pfizer’s reputation. After Moderna, which had taken large US government grants, agreed a much lower price, Pfizer eventually settled on $19.50 a dose in the initial contract with the US, and equivalents in other western countries. But this was effectively four times the price of J&J’s single dose shot, and five times higher than a dose of AstraZeneca’s.

Production capacity is key

Pfizer’s vaccine success has been built not on research brilliance, but on manufacturing nous.

As Pfizer’s production capacity soared in 2021, the company grabbed market share from cheaper rivals AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson. Pfizer’s strategy to keep more of its production in-house paid off. Along with BioNTech, they had nine of their own facilities, with the largest in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and Puurs, Belgium, as well as 20 contract manufacturers. It went to extraordinary lengths to secure production. When Pfizer was unable to find appropriate ultra cold storage for its vaccines while in transit, it designed a thermal container itself. In order to secure dry ice to cool them, it built its own dry ice factory.

This combination of control and expertise enabled a dramatic productivity leap. When Pfizer first began to supply the vaccine, it took an average of 110 days from the start to putting vaccine into a vial. Now, it takes an average of 31 days. In January, it said it could deliver 2bn doses this year but by August, it said it was on track to manufacture 3bn. Next year, it plans to make 4bn doses.

In contrast, AstraZeneca struggled to scale up production. The Anglo-Swedish drug company, which had partnered with the University of Oxford, had planned to deliver 300m doses to the EU in the first six months of this year. But after a series of problems, it cut its deliveries dramatically, to just 100m. EU politicians were so irate they took AstraZeneca to court.

The problems were replicated at J&J, which at one stage paused its EU rollout.

EU leaders needed vaccines to keep their people safe — and to restore their own reputations — and Pfizer looked like the only reliable supplier in the room.

“Politicians have been badly burnt. The few of them who have tried to negotiate on price or other forms of access have been politically hurt, particularly in the EU where after the early rollout there were enormous recriminations,” says Gostin. “People asked ‘Why didn’t you give companies what they are asking for?’”

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the EU Commission, began calling and texting Bourla in January 2021. When, in the spring, it became clear Pfizer would have more doses available, she began to negotiate a mega-deal of up to 1.8bn shots to be delivered all the way until 2023.

“The member states wanted access to the vaccine for the next few years and to lock that down early,” says Sean Marett, BioNTech’s chief commercial officer, who adds that price was not the critical issue in the talks. “I think what was important was reliability and dependability. People were scared. You could feel it. Europe was worried about lockdowns and variants and wanted to reassure people.”

The EU now expects five times more doses from Pfizer than its next biggest supplier, Moderna. Such a huge commitment would usually result in a price cut. But Pfizer raised the price by more than a quarter from the initial agreed level of €15.50 to €19.50 — and von der Leyen agreed.

Pfizer also raised the price by a similar amount in its 2021 contracts with the US and the UK.

Jillian Kohler, the director of the WHO’s collaborating centre for governance, transparency and accountability in the pharmaceutical sector, says Pfizer had historically had a reputation for being “quite aggressive” and “interested in profit maximisation at the expense of everything else”. But the pandemic has amplified its power, “exacerbating Pfizer’s ability to ask extraordinary demands from governments”.

Pfizer has told investors it will be able to raise the price after Covid-19 enters an endemic phase, when its spread is slower and more controlled. Analysts are cautious about assuming it will dramatically hike the price, wary that Pfizer could face more competition.

But Pfizer’s dominance looks increasingly secure as other vaccines are delayed or abandoned. It is the only one of the pre-pandemic big four vaccine makers currently selling a shot: Sanofi and GSK have not yet reported their phase 3 data after a dosing mistake set back an earlier trial of their joint vaccine, while Merck left the race in January after poor results.

Next year, Pfizer forecasts it will generate $29bn from the vaccine, based on contracts it had already signed in mid-October. In an earnings call in February 2021, Pfizer predicted that after the pandemic ends, its current margins — in the high 20 percentage points — will increase, as costs are likely to fall.

“There’s a significant opportunity for those margins to improve once we get beyond the pandemic environment that we’re in,” said Frank D’Amelio, chief financial officer.

African countries struggle to get supplies

Bourla insists he is not focused only on the bottom line. “I’m satisfied that the company is doing financially very well, but even more satisfied when I go into a restaurant and get a standing ovation because everybody feels that we saved the world,” he told Yahoo Finance in July.

Winnie Byanyima, the Ugandan who runs the UN’s global effort to end Aids, shuddered when she read that interview. “He hasn’t saved the world. He could have done it but he hasn’t,” she says, pointing to the very low vaccination rates in Africa.

Pfizer has slashed prices for low-income countries, to as low as $6.75 per dose for the poorest, and about $10 to $11 for middle income nations, less than Moderna is charging but still higher than AstraZeneca.

Yet even if that makes the doses more affordable, many leaders feel Pfizer is forcing them to navigate a labyrinth in order to obtain them. While western leaders had Bourla on speed dial, the first challenge for some nations was getting his — or anyone at Pfizer’s — ear.

“Countries reported to us that they had been trying to get hold of Pfizer and no one returned their calls,” says a person familiar with the African Union’s vaccine-purchasing operation.

Before deals could be agreed, Pfizer demanded countries change national laws to protect vaccine makers from lawsuits, which many western jurisdictions already had. From Lebanon to the Philippines, national governments changed laws to guarantee their supply of vaccines.

Jarbas Barbosa, the assistant director of the Pan American Health Organization, says Pfizer’s conditions were “abusive, during a time when due to the emergency [governments] have no space to say no”.

But negotiators feared that pushing back could delay the delivery of doses. Jonathan Cushing, head of global health at Transparency International, says: “It is effectively a race to the bottom: whoever signs over the most, will get the vaccines quickest”.

Susan Silbermann, the former head of Pfizer vaccines who created the company’s Covid-19 task force, says the company knew it was not going to be able to supply the whole world in the initial phase.

“We found that governments were at different stages of establishing specific pandemic procurement processes. It wasn’t that we wanted to contract with country x or country y first, we were having multiple conversations at the same time. It was often about how quickly governments responded,” she says.

The negotiations with South Africa were particularly tense. The government complained that Pfizer made what its former health minister Zweli Mkhize called “unreasonable demands”, which it said delayed the delivery of vaccines.

At one stage, it had asked the government to put up sovereign assets to cover the costs of any potential compensation, something it refused to do. The Treasury rejected the health department’s request to sign the deal with Pfizer, according to people familiar with the matter, arguing it was equivalent to “surrendering national sovereignty”.

But Pfizer did insist on indemnity against civil claims and required the government to provide finance for an indemnity fund.

“The South Africans said to me: ‘These guys are putting a gun to our head,’” says a senior official familiar with African vaccine procurement efforts. “People were screaming for a vaccine and they signed whatever was put in front of them.”

Fatima Hassan, founder of South Africa’s Health Justice Initiative, says the health ministry was ill-equipped to negotiate with a “lawyered-up” pharmaceutical company like Pfizer. Her organisation is preparing to go to court to force the publication of unredacted contracts signed between Pfizer and the South African government.

“We want to know what else they played hardball on,” says Hassan. “A private company can’t have so much power. The contract should be open. They would tell the story of what Pfizer has managed to extract out of sovereign countries around the world.”

A senior South African government official would not comment on Pfizer specifically, but adds: “I think it’s immoral for anybody to profiteer to the extent that has happened out of a serious crisis for humanity as a whole.”

The next twist came when the company refused to release doses until it had inspected if the nations had the infrastructure to deliver the ultra cold vaccines. Pfizer had a good reason to worry: even many western healthcare providers had struggled to store the shots. Silbermann says Pfizer had a responsibility to help governments understand the requirements because “no vaccine is any good if it sits in a container”.

But one senior leader at Covax, the WHO-backed programme delivering vaccines to the developing world, says some governments felt Pfizer overstepped its bounds. “Some countries thought they had it all covered and then Pfizer either included other things or wasn’t satisfied with what they had done,” he says.

In September, Bourla enraged many by suggesting that vaccine supply will be so plentiful by next year that vaccine hesitancy will become the limiting factor. “The percentage of hesitancy in those [low-income] countries will be way, way higher than the percentage of hesitancy in Europe or in the US or in Japan,” he said.

There is some evidence to support this: South Africa, which faced shortages earlier in the year, is now struggling to persuade some people to take the vaccines that are available. But it added to the impression that Bourla is out of touch with the realities of life in an unvaccinated country. Tom Frieden, the former director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, describes this comment as “egregious”.

“It is on a par with people in the Aids crisis saying Africans wouldn’t be able to take antiretrovirals because they couldn’t tell the time,” he says. “It was shockingly irresponsible.”

Without any visibility into Pfizer’s order book, or whether there even was a queue, some governments began to suspect that these extra conditions were delaying tactics. Bruce Aylward, a senior adviser at the WHO, says vaccine makers are clearly not prioritising Covax.

“Show us the queue. Where is the order? And how do you organise your queue? If it is by the order in which they were placed, then we would have been served a long time ago,” he says.

Pfizer said it is transparent with its delivery schedules. It said it seeks the same kind of liability protection it has in the US and if countries are unable to provide it then it works with them to find “mutually agreeable solutions”.

The company said it contacted countries at all income levels and that “fair and equitable distribution was our North Star from day one”. But after its initial outreach it said it found that the majority were reserved by high income nations, often because poorer countries preferred vaccines without tricky cold chain requirements.

“We’ve seen the supply balance weigh in favour of low and lower-middle income countries in the second half of 2021,” it added.

Aurélia Nguyen, managing director of Covax, says Pfizer has hit its targets for delivering supplies to the programme. But she adds: “From our initial contact with Pfizer, it became clear early on that the best Covax could expect was minimal doses in 2021.”

Aylward says Pfizer was not fast enough but should be given credit for stepping up this autumn. Vaccines have now been delivered to 161 countries. It has provided over 740m doses to low and middle-income nations in 2021, about 100m of which come from the Biden administration’s donation. Pfizer has promised another billion in 2022.

Richard Hatchett, the chief executive of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovations, one of Covax’s backers, says he thinks the world owes Pfizer, Moderna, BioNTech, AstraZeneca and many others in the industry “a huge vote of thanks”.

All he wants, for the limited duration of the pandemic, is to see the order books. “If everybody’s being above board and you’re just delivering in the sequence of when things were paid for an order, then transparency shouldn’t be a problem,” he says.

“It would take some of the heat out of the room . . . the pitch of emotions over these issues are very, very high for obvious reasons. I mean, people are dying.”

The vaccine blame game

Almost a year after the first Covid-19 vaccines were approved, the shots have changed the lives of more than half the world. Some 54 per cent of people have received at least one dose. But they remain frustratingly out of reach for 94 per cent of residents of low-income countries.

The stark evidence of inequality has sparked a blame game. Some government officials point the finger at Pfizer and Moderna, asking why the companies are not giving more priority to the neediest countries, rather than selling booster shots to wealthy nations.

Frieden, the former CDC director, says governments often “sweeten the pot” for vaccine manufacturers to get the shots they need: they fund research and development, train clinicians, educate the public, and buy billions of doses. In return, they expect vaccine makers to behave responsibly. However he says it is “striking” the degree to which Pfizer and Moderna have not.

“There are certain unwritten rules about how vaccine manufacturers act and how governments act. Vaccine manufacturers have broken these rules, so maybe they should be rewritten,” he says.

In his public statements, Bourla has often put the onus on low and middle-income countries, Covax and the WHO, to sign up for deliveries. On an earnings call at the start of November he warned that, once again, wealthier nations were snapping them up.

“Again, the low and middle-income countries will be behind in deliveries because they didn’t place their orders,” he said.

But for some critics and health experts, the blame lies less with the companies and more with wealthy governments which have put their own people first and shirked their responsibility to ensure broader distribution of vaccines.

Through the course of 2020, western politicians failed to fund Covax quickly enough for it to move fast when vaccines became available, or to put clauses in their contracts that companies must help poorer countries. The shaky starts to the deliveries of vaccines, such as the delays suffered by the EU, put politicians on edge, encouraging them to hoard.

“Countries learnt that they preferred to have orders for doses they didn’t need,” one former Pfizer executive says. “A lot of politicians got a lot of negative press about not being prepared for a pandemic.”

Thomas Cueni, director-general of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations, says it is up to governments with surplus doses like the US, UK, EU and Canada to make sure that Covax gets the shots it needs.

“The way forward is for these governments, who know their vaccination rollout status better than anyone, to co-ordinate dose sharing and give priority to Covax to urgently address vaccine inequity,” he says.

Even inside western governments, some wish they had done more. “We shouldn’t have left it up to the companies to figure it out. We should have incentivised them for a global mission,” says one US official.

Governments often did not work together. At one stage in 2020, the Trump administration even started to withdraw from the WHO. Hatchett says the rollout has suffered because of a lack of a “centre of power”.

“You’ve got a highly diffused set of governmental authorities who, to some extent, are competing with each other for vaccines. Even when they can pay for it, they’re competing with each other to get their orders,” he says. “The UN and the WHO can’t force anybody to do anything.”

The race to vaccinate the world has been complicated by rich countries’ booster programmes. Boosting is now well under way: Israel has already given a third dose to 44 per cent of its population, the UK has done 22 per cent, and the US just over 10 per cent.

Even before the emergence of the Omicron variant on Thursday, these booster programmes looked set to cement Pfizer’s dominance of the Covid vaccine market because of the high efficacy of its shot and the company’s success at production. The rapid expansion in booster plans that some western governments have announced in recent days will only entrench its position further.

Pfizer has launched a “Science will Win” ad campaign, while Bourla is writing a book about the “moonshot”. He insists that Pfizer is in a position of “commercial strength” in the Covid vaccine market, with people likely to need boosters year after year.

Bourla told investors this month that Pfizer had touched more lives than any pharmaceutical company before — and that its $80bn in forecasted revenues this year is likely a record for any drugmaker ever.

Geoffrey Porges, an analyst at SVB Leerink, an investment bank that specialises in healthcare, says this financial firepower will fuel Pfizer’s growth for years. “It is a once-in-an-epoch economic windfall,” he says.

Additional reporting by Kiran Stacey in Washington, Oliver Barnes and Sarah Neville in London, Erika Solomon in Berlin, Nikou Asgari in New York, Mehul Srivastava in Jerusalem, and Sam Fleming in Brussels

Letters in response to this article:

A shareholder activist pleads for vaccine equity / From Lauren Compere, Managing Director, Boston Common Asset Management, Boston, MA, US

Comments