Plastics-to-oil recyclers face a double struggle

Simply sign up to the Energy sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

At a recycling plant in Swindon, 80 miles west of London, an experiment to turn used plastics into oil is under way. If successful, the portable “chemical recycling” plants used in the process — designed to fit into shipping containers — will one day be sold worldwide.

Some 350m tonnes of plastic a year are produced globally, with production forecast to triple by 2050 and account for a fifth of global oil consumption, according to research company Statista.

Driven by pressure to cut the world’s reliance on finite fossil fuels, chemical recycling pioneers hope that producing oil from plastic waste will provide an alternative source of hydrocarbons.

“Chemical recycling of plastics is a niche solution but it is getting extraordinary attention from the largest petrochemical companies and consumer brands,” says Ben Dixon, head of circular materials at Systemiq, a consulting and investment group. “Does this herald the start of a revolution? Quite possibly — ultimately, that depends on developments in the technology and economics of recycling, wider developments in the waste system and regulatory support for this nascent industry.”

The Swindon plant is operated by Recycling Technologies, a UK business that employs about 130 staff and has raised nearly £40m in equity and grant funding since its creation a decade ago.

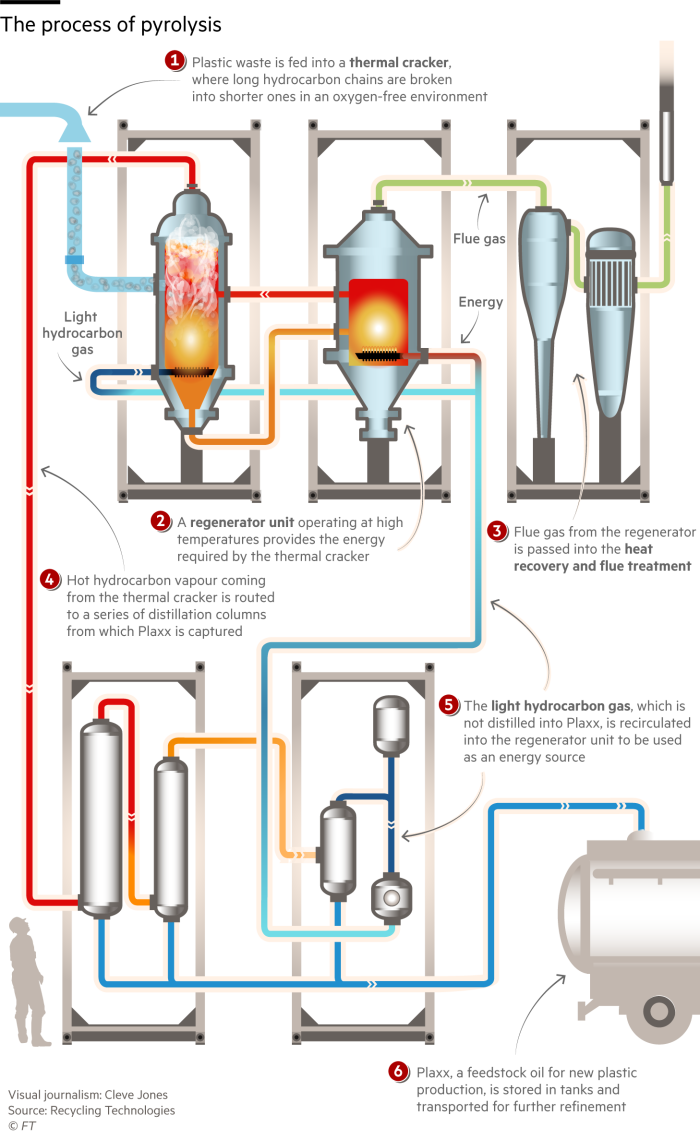

Recycling Technologies’ plant uses pyrolysis, a process in which polymers are broken down with extreme heat. Its RT7000 machine heats mixed plastics in the absence of oxygen — a process known as “cracking” — to produce gas. Through distillation, this vapour is turned into products ranging from heavy wax and oils to light oils and gas. These can provide the building blocks for new polymers, or be used as fuel.

An RT7000 can turn 7,000 tonnes of plastic — including hard-to-recycle waste such as polystyrene and flexible packaging — into 5,250 tonnes of liquid oil, called Plaxx, annually. Recycling Technologies sends 70 per cent of its Plaxx to Neste, a Finnish producer of sustainable fuel and plastic feedstock. The remaining 30 per cent of the Plaxx is used as a wax equivalent to make candles and paint, while the leftover gas and char are consumed as energy sources within the process.

Adrian Griffiths, founder and chief executive of Recycling Technologies, hopes to expand operations beyond Plaxx production and sell RT7000s to waste companies globally, plus management and support services. He believes the technology could help displace virgin oil in plastics manufacturing.

“In Europe, there is now a fiscal stimulus to make sure it doesn’t matter what the price of oil is if there is a significant demand for recycling plastic back into the oil,” he says. “The problem with this is Europe represents only . . . a small part of the global picture. Our ambition is to get the capital costs down . . . by mass producing that machine.”

But environmental groups query the green credentials of chemical recycling given its energy use and end products.

“A lot of projects and facilities claim they do chemical recycling but if you look at what they do with the output — the final oil-based product that comes out — it is sold as a fuel, so it is not even recycling,” argues Sander Defruyt, head of plastics at the Ellen MacArthur foundation, a non-profit group focused on the circular economy.

More stories from this report

Energy grids of the future steeled for big changes

Carbon capture eyes renewed backing despite past failures

Gas prospects lose steam as low-carbon shift gathers pace

Low-income countries play carbon leapfrog

Carbon price is missing from Biden’s overhaul of climate policy

Positive outlook for batteries in Australia renewables shift

According to consultancy McKinsey, however, pyrolysis has a lower carbon footprint than plastic incineration, even if its energy use is not insignificant. Also, customers have shown a willingness to pay extra for recycled products — so not all the end-product will become fuel.

“There is a significant green premium in the market today, with prices for recycled polyethylene above the price of virgin [oil-based] resin,” says Jeremy Wallach, a partner at McKinsey’s chemicals practice. “While the recycled oil can be blended into fuels and burnt (as diesel), its potential higher value in plastic applications, linked to ‘green premium’, suggests plastics will be a primary outlet as the industry scales up.”

The Swindon plant is one of a growing number of facilities seeking a viable method of turning plastics into substances of value.

Mura Technology, a British plastics recycling group, is building a plant in Teesside, north-east England, that uses a hydrothermal process, called HydroPRS. This works by injecting steam into mixed plastics, allowing the heat to spread evenly and quickly. Mura’s process converts waste plastic into naphtha, distillate gas oil, heavy gas oil and heavy wax residue. It also creates a gas that powers the machine’s boilers.

Steve Mahon, Mura’s founder and chief executive, says its products cost the same as those made from fossil fuel.

Nevertheless, big obstacles — scalability, poor waste collection infrastructure, high set-up costs, and uncompetitive pricing when crude oil is cheap — must be overcome to make this recycling viable.

“Without a green premium, oil prices above $65 per barrel are likely required to justify the investment economics,” says Wallach. “However, with a green premium, the economics of chemical recycling begin to decouple from oil and can be attractive at lower oil prices.”

Griffiths points to the renewable energy sector as a model for how the chemical recyclers might scale up.

“Like with solar and wind, there was a time when the cost of installation was never going to compete with power stations,” he says. [So you had] contracts for difference and feed-in-tariffs. You don’t need those any more because wind and solar are below the levelised cost of electricity.” Chemical recycling, he says, “is going to be exactly the same thing.”

Comments