Inventors learn to deploy their assets as collateral

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Unheard of two decades ago, the concept of using intellectual property assets as collateral has seeded itself firmly in the financial sector.

The strategy first surfaced among borrowers during the dotcom bust in the early 2000s and became even more accepted by lenders after the 2008 financial crisis.

The deployment of patents and other forms of intellectual property to secure financing has continued to grow since — and financial distress and strained credit lines created by the coronavirus downturn could give the collateralisation strategy another boost.

In most cases of corporate borrowing, IP may not serve not as the dominant collateral but it can still act at an important asset in inducing lenders to offer more money on better terms.

“In an economic downturn, cash is king. Looking for assets is critical to that. IP assets [are] valuable, and you are looking at those to get liquidity,” says Nick O’Grady, a partner in Baker McKenzie’s London banking and finance team. Lenders in Europe, he says, are happy to look at these opportunities “as they arise”.

Household names such as Alcatel-Lucent, General Motors and Dell are among borrowers that previously deployed the strategy.

But loan demand is likely to accelerate among smaller businesses during this downturn, says George Summerfield, a patent litigation partner at K&L Gates in Chicago. For them, their “only assets may very well be their intellectual property,” he says.

The use of patents as collateral has grown significantly in the past five years, according to William Mann, an assistant professor of finance at Emory University in Georgia, US. His analysis is based on data from the US Patent and Trademark Office. The number of patents recorded by the USPTO as having ties to a “security interest” or “security agreement” almost doubled to 400,000 during the four years ending in 2019 when compared with the prior four years, he says.

That calculation “actually understates the magnitude of activity”, Mr Mann says. This is because it fails to capture the patents collateralised under scenarios in which borrowers simply issue “negative pledges”. These commit borrowers to making no attempt to wrest IP assets back from lenders’ control in the event of a bankruptcy. Such arrangements are less formal, but nonetheless represent an increasingly popular way — particularly among start-ups — to structure financing deals, he says.

Despite its growing acceptance, IP-backed lending remains an exception, not the rule. “IP is not the first asset that comes to mind, unless you are an IP attorney,” says Jaime Vining, partner at Florida law firm Friedland Vining. But that could change in this downturn as more companies need liquidity, she predicts. “Companies are looking for creative solutions.”

Patent values can show “more resistance to a downturn”, particularly when compared with other IP assets, says Maria Loumioti, an assistant professor at Dallas’ Naveen Jindal School of Management. But lenders must typically engage in painstaking due diligence before accepting patents as collateral, says Prof Loumioti.

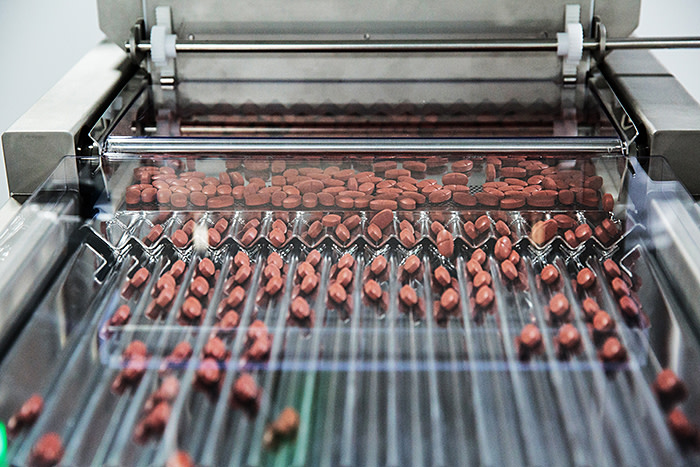

Lenders like drug patents that can be translated into predictable sales revenue. But they may accept trademarks as collateral more quickly than patents. A trademark’s potential to generate revenue “can be proven easily”, says Mathias Schumacher, expert on business valuations at corporate advisers Duff & Phelps.

Other IP assets typically require more due diligence by lenders. “The first question becomes, is the lender even equipped to understand what it has? . . . I’ve found that a lot more often than not, it really isn’t,” says Mr Summerfield of K&L Gates. But he adds: “Among people who are in the business of lending money, especially to high-tech companies, the recognition is that intellectual property assets tend to be the thing that provides the most potential for value.”

Comments