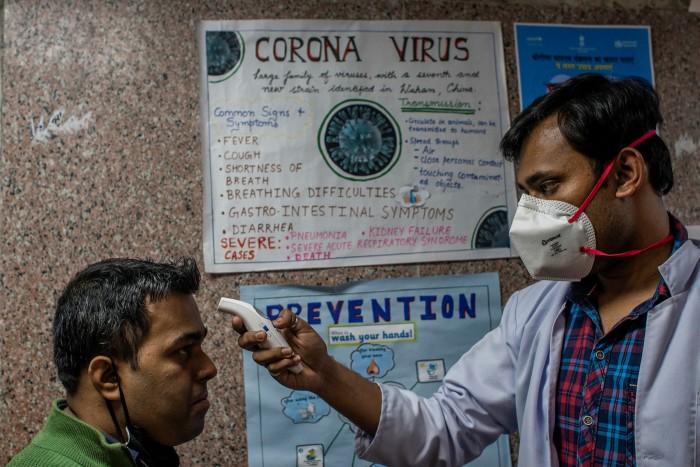

Covid delays India’s attempts to curb widespread overuse of antibiotics

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When a leading medical journal warned against seeking treatment in Indian hospitals because a drug-resistant superbug had emerged there in 2010, the country’s medical and political establishments were incensed.

The government took particular umbrage at the scientists’ decision to name the gene that made the bacteria antibiotic-resistant after New Delhi.

Yet today, India no longer denies its serious challenges with antibiotic resistance. With a chronically underfunded healthcare system, a shortage of doctors and other trained staff, as well as a high burden of infectious disease, India has many of the vulnerabilities that drive antibiotic overuse — and ultimately fuel resistance.

Indian authorities have vowed to tackle the problem. In a national radio address in 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi urged Indians not to take antibiotics without a doctor’s prescription and warned of the growing threat of drug resistance. New Delhi has rolled out a detailed national action plan for combating antimicrobial resistance, which it acknowledged as “a major public health concern”.

“In hindsight, it was a very good thing that paper came out,” microbiologist Kamini Walia, who studies antimicrobial resistance at the Indian Council of Medical Research, says of the offending article, which was published in The Lancet. “It jolted the country into accepting something that was going on for a very long time.”

But for all the high-level rhetoric, experts say the real efforts, and funding, to curb antibiotic overuse in healthcare has been insufficient, even before the coronavirus pandemic diverted all the attention of the Indian government and healthcare system. “A lot of the things that need to happen are pretty straightforward — they just required a bit of attention and focus,” says Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy in Washington. “But not enough has been done. It remains a gaping hole.”

As in many developing countries, India’s poor hygiene and inadequate sanitation systems leads to a high burden of infectious diseases, including respiratory infections. Despite efforts at universal childhood immunisation, vaccine coverage for childhood diseases is only about 65 per cent. Chronically underfunded public hospitals and erratic private hospitals struggle to cope with demand.

With their prices controlled by the state, antibiotics are cheap and easily obtained, without a doctor’s prescription, from a vast number of poorly regulated pharmacies. “It’s a demand side issue,” says Indu Bhushan, chief executive of Ayushman Bharat, India’s national health insurance scheme. “A lot of people actually take antibiotics as soon as they get fever or cold or cough, and they don’t complete their course, which is also a problem.”

Doctors also routinely prescribe antibiotics for patients, without ever ascertaining whether they are genuinely warranted, partly because medical diagnostic services such as blood tests are expensive, and the infrastructure is scarce outside big cities. “Doctors don’t have enough training and they just tend to prescribe blindly so the patient feels satisfied,” says Ms Walia. “Giving the antibiotic is cheaper and easier than asking a person to get a test.”

Poor hospital infection control encourages overuse of antibiotics by doctors seeking to prevent patients catching infections in hospital. “No doctor wants his patient who has undergone surgery to get hospital-acquired infections so they give three, four or five antibiotics to get patients safely out of hospitals,” says Ms Walia.

To tackle these problems, the ICMR has developed an antimicrobial stewardship program in 30 hospitals as part of its disease surveillance networks. The initiative has involved in-depth training, appropriate staffing, creation of infection control committees and new protocols to encourage more appropriate use and monitoring of antibiotics.

Participating hospitals are now being asked to mentor personnel from eight to 10 other nearby hospitals in antimicrobial stewardship, in a bid to spread awareness and best practice.

But progress has been slow, and that was before the government and health system’s attention was diverted to battling the coronavirus pandemic. Most other healthcare programmes — including childhood immunisation campaigns — have been put on the back burner.

Ms Walia says coronavirus — known to have so far infected more than 9.7m Indians — has also fuelled another wave of antibiotic overuse. “All kinds of antibiotics are being prescribed left, right and centre,” she says. “The problem of antimicrobial resistance is going to escalate post-Covid.”

Part of the problem, experts say, is that in contrast to coronavirus, antimicrobial resistance is a hidden killer, whose victims are never recognised or counted. That has made it tough to muster real political will and meaningful resources to tackle it.

“The media hasn’t really been able to make antimicrobial resistance a people story,” says Mr Laxminarayan. “It is still very much a science story. Unless people connect it to their own lives or understand what they stakes are for their own health, there is unlikely to be much policy action.”

Other resources

AMR data is incomplete, infrequently updated and often available only after a significant time lag. Some important additional sources and ways to visualise the trends are:

The Global AMR R&D Hub, which is co-ordinated by the German Centre for Infection Research, tracks investments in research

The Tripartite AMR Country Self-assessment Survey tracks the status of national plans to tackle drug resistance

Resistance Bank collates data on antibiotic resistance detected in animals, with a focus on low and middle income countries

Comments