British designer Paul Cocksedge: ‘You respond to the space’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When the designer Paul Cocksedge was told he had to move out of his east London studio early last year, he decided to make something of it. Literally. Hiring his own core drillers, he started to remove cylindrical blocks from the studio floor. “We’d been here for over 10 years,” he says, “and I wanted to keep some of it for myself, take it with me. A lot had happened here.”

What started as something of a protest against the gentrification of an area that had once been synonymous with cheap rents and creativity, as well a romantic act of memory, also turned into a piece of urban archaeology. The drilling revealed layers of London history, the material below his floor turning from concrete filled with stony aggregate to clay bricks over 100 years old. Once polished, the cylinders became elements of furniture — the smallest as supports for glass shelves, the longest as legs for a glass-topped table — which went on show at last year’s Salone in Milan, the city’s annual furniture fair. The studio interns might have been thrown by the experience: “They thought they’d come to work on [the drawing software] CAD, and then I handed them a drill,” laughs Cocksedge. In fact, they’d helped create one of strongest bodies of work to be shown in Milan that week.

Thanks to Brexit, I find Cocksedge in the same studio just a few weeks ago, a ramshackle workshop filled with prototypes and tools. The UK’s uncertain future has halted, if not reversed, the escalation of land values in Hackney, and Cocksedge’s landlord has decided to delay any development of the studio’s site. In the meantime, the designer has refilled the 1,500 holes he made last year, though ghostly traces are visible beneath the newly applied grey floorpaint.

The latest project to emerge from here is an installation that will function as the Swire Properties VIP Lounge at Art Basel Hong Kong, a pop-up space situated on the first-floor concourse of the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre. The location is as inauspicious as it sounds, but the 40-year-old Cocksedge likes a challenge. This is a man, after all, who’s constructed a table out of two identical L-shaped wings of sheet steel, its 500kg perfectly balanced where the two upright surfaces join. It now belongs to an American collector.

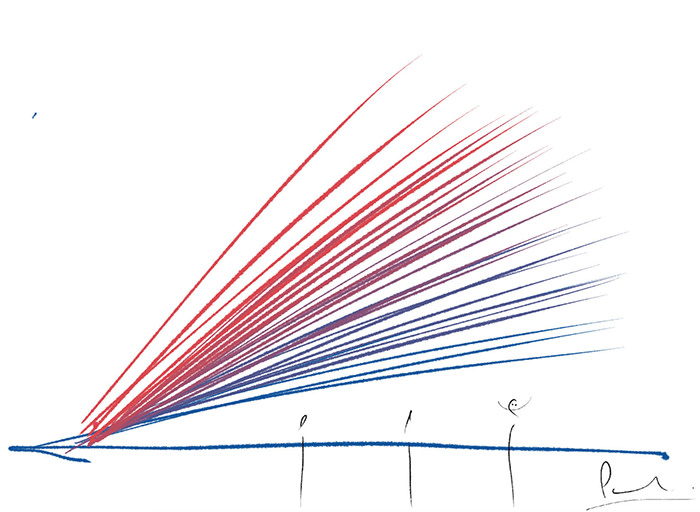

“You just have to respond to the space you’re given,” he says, jumping up to grab a makeshift model — a rough block of wood, where brightly coloured rubber bands are wound around three dowel rods to form a triangular shape. “And this one in Hong Kong has huge columns in it, so we decided to use them.” For the job itself, the rubber bands will be replaced by webbing — the sort used for slacklining ropes — in a blue and red that will be wound around the columns to create a triangular central volume.

“So many exhibitions invest a lot in materials which then get thrown away after just a few days. We’ve tried to dematerialise the installation as much as possible. The webbing could even be used again.”

Art lovers, meanwhile, will notice similarities between Cocksedge’s solution and the work of artists like Fred Sandback and Lygia Pape, who used string to create finely drawn volumes in space.

This project is sponsored by Swire Properties, the Hong Kong developer with whom Cocksedge has worked before, animating the cavernous atrium of a shopping mall in Shanghai with a permanent installation of hundreds of furled Corian pieces, like sheets of paper caught in a flurry of wind. His studio relies on these one-off commissions. He’s about to take on another atrium, this time in an apartment block in London’s Stratford, for a London developer he met at a design dinner. Another new installation illuminates the new flagship store of Cos in King’s Cross: six rings of light hung inside a long window which come to life as the sun goes down at night.

He has worked like this ever since he graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2002, and set up his studio with Joana Pinho, a visual communications graduate. “At Christmas, when you stop working for a bit, you do think: ‘What’s next?’,” he says. “It’s not exactly like I have a plan.”

In New York, Cocksedge is looked after by the design gallery Friedman Benda, which has helped deliver some of his more wilful (and expensive) projects. They include “Freeze”, a series of furniture he started working on in 2014, fusing together a range of metals through freezing. The first experiments involved a trip to Austria, where he buried an aluminium table top and copper legs on a mountainside in deep snow overnight. (The process can be replicated with liquid nitrogen.) Since then, he has been working with the biggest manufacturer of toilet doors in North America to make the same process viable for fitting out prisons, schools, airports and cafés. “One thing leads to another,” says Cocksedge. “The toilet door guy saw the ‘Freeze’ project in a copy of Wallpaper magazine that he’d picked up on a plane.”

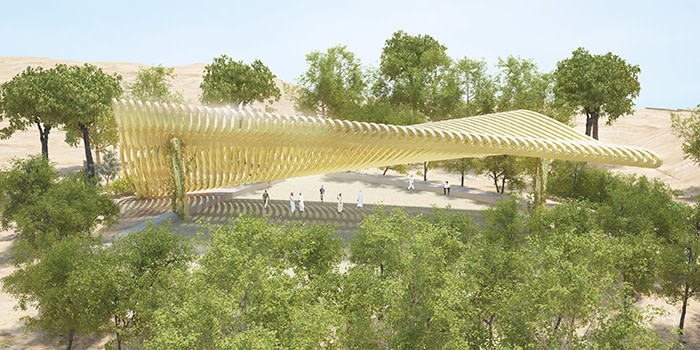

He is working on the interior design for a new sportswear brand in Milan, and a perfume bottle for a Korean company. In Oman, he is creating a canopy for the world’s largest botanical gardens, which will provide both a view of the sky and shade throughout the day.

But Cocksedge is fundamentally a free spirit and a self-starter — somewhere between an activist, designer and inventor. He seems happiest combing the local streets for inspiration. When his bike lights kept being stolen, he came up with the Double O, a circular LED model that you can pop in your pocket, and which also creates a softer and better diffused light for the cyclist. And after continually finding speakers abandoned around his neighbourhood, he raised £101,000 on Kickstarter, and created a small cube in a soft plastic that houses a battery, Bluetooth and an amplifier, which can be popped on top of the most battered old piece of kit.

“People were buying these Beats by Dre things for £200,” he says. “But that’s just about restyling. The sound was perfected years ago.” The Vamp costs £49 and so far they have sold 10,000. By way of demonstration, Cocksedge connects his iPhone to the small red cube, pops it on top of a single down-at-heel speaker, and The Rolling Stones’ “Can’t You Hear me Knocking” reverberates around the studio. VIP lounges are all very well, but the Vamp looks more like the future to me.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments