What a debt ceiling deal means for the US economy

Simply sign up to the US economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It’s not quite a done deal. Congress will vote on the “Fiscal Responsibility Act” tomorrow, and the Senate probably by Friday. But it looks like the US will once again stop punching itself in the face just before needing hospitalisation (for two years at least).

We discussed the financial implications of the deal yesterday, with the US government needing to issue a deluge of Treasury bills to rebuild its reserves in the coming months, and the impact that could have on funding markets.

But here’s Goldman Sachs on the fiscal and economic implications of the slight austerity that the deal entails:

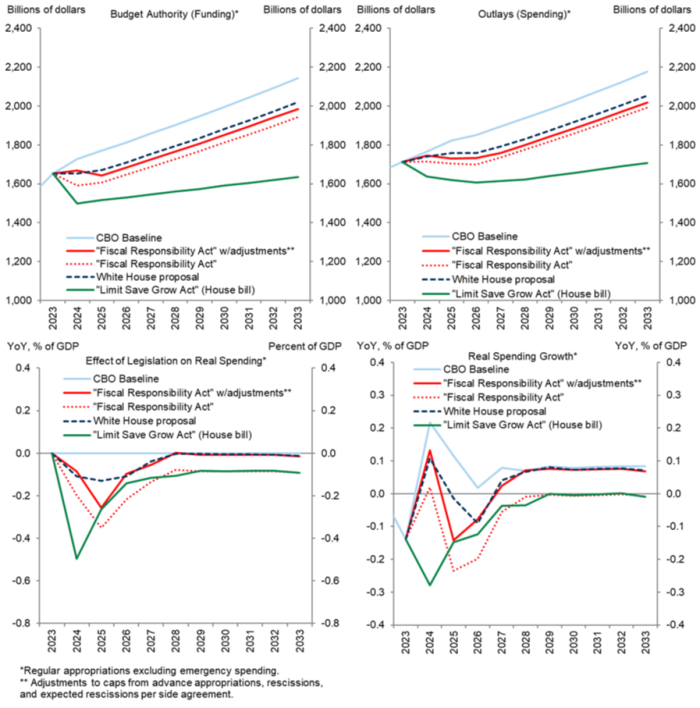

The main source of budgetary savings in the deal is a two-year cap on federal discretionary spending. Congress appropriates this segment of spending annually and it accounts for around 25% of total federal spending, with slightly more than half dedicated to defense and the remainder to other “non-defense” spending (generally domestic programs outside of the major benefit programs). We expect the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) will estimate that the spending caps in the deal will reduce discretionary spending by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years and reduce interest expense by around $160-170bn over that period. On paper, this would reduce projected deficits over the next decade by an average of 0.4-0.5% of GDP.

That said, the actual spending cut is likely to be much smaller, for two reasons. First, the caps apply for only two years, so most of the projected savings will depend on policy decisions made after the next election. (The description of the deal states that caps apply for 6 years, but they are only enforceable via sequestration for 2024 and 2025 and should have little effect thereafter.) Second, the deal included other details that lessen the effect of the cuts, particularly in 2024. This includes counting the bill’s rescissions of unused COVID funding against spending for the coming year, pre-funding certain items so the spending is excluded from the caps, and a side agreement that $20bn in IRS enforcement funding that would have been spent later in the decade will be redirected toward domestic spending without counting toward the cap. With these adjustments, the White House has indicated it believes non-defense spending will be roughly flat in nominal terms in FY24 compared with this year.

Here is all that in chart format, shown relative to the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline scenario, and the likely impact of alternative plans like the White House’s original proposal and the Republican “Limit Save Grow Act”.

Aside from the headline fiscal restraints, the deal will also affect more specific issues like student loans, work requirements, and environmental reviews, and introduces a (toothless) pay-as-you-go rule for the US government.

Here’s Goldman’s Alec Phillips:

The agreement prohibits the Biden Administration from extending the pause on student loan repayments in place since March 2020, but it does not block the Administration’s student loan forgiveness plan, which the Administration announced last year but has not yet implemented. Late last year, the Administration extended the repayment pause, which postpones roughly $5bn per month in student loan repayments, until 60 days after the Supreme Court ruled on the separate $400bn loan forgiveness plan the (the Supreme Court is likely to rule on loan forgiveness in June, so this likely would have meant a restart of payments after August 2023). The debt limit agreement prohibits further extension of the payment pause, but is silent on the student loan forgiveness plan. Prior to the announced debt limit deal we had already assumed the repayment pause would end on schedule, though there was clearly a chance the White House might have extended it once again. The debt limit agreement eliminates that possibility and should result in a restart of student loan payments in September 2023.

The bill also includes a few narrower policies that look likely to have a limited macroeconomic impact:

– Work requirements. The bill would incrementally modify work requirements under Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as welfare and food stamps. No official savings estimate from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is available, but we expect the overall fiscal effect of these changes to be relatively minor.

– Environmental reviews. The bill includes policies to incrementally streamline reviews for infrastructure projects under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). These are generally seen as a down payment on broader energy permitting reform that could be attached to other legislation later this year.

– Executive PAYGO. The debt limit deal also codifies a “pay-as-you-go” (PAYGO) rule for executive branch rulemaking, requiring federal agencies to offset any policy action that increases direct spending by more than $100mn/yr with another policy to cut spending at least as much. However, the Director of the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has power to waive the requirement and decisions could not be reviewed by courts, so it is unlikely to have much practical effect.

The tl;dr (which admittedly might have been more useful to have at the top) is that most of these restraints and measures were probably coming anyway through normal budget sausage-making, and won’t have a huge fiscal or economic impact.

Oh and with the debt ceiling suspended to January 2025 and “extraordinary measures” then available (assuming the government’s account with the Fed has been fully replenished) the next debt ceiling deadline is probably around this time 2025. Yay . . .

Comments