Film and art meet in Los Angeles

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In Los Angeles, film and contemporary art meet mostly in the collections of movie stars. Leonardo DiCaprio has haunted art fairs and auctions to pick up work by Takashi Murakami and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The holdings of Brad Pitt extend to Banksy, Dom Pattinson and more. But beyond celebrity acquisitions, in California the two worlds rarely collide.

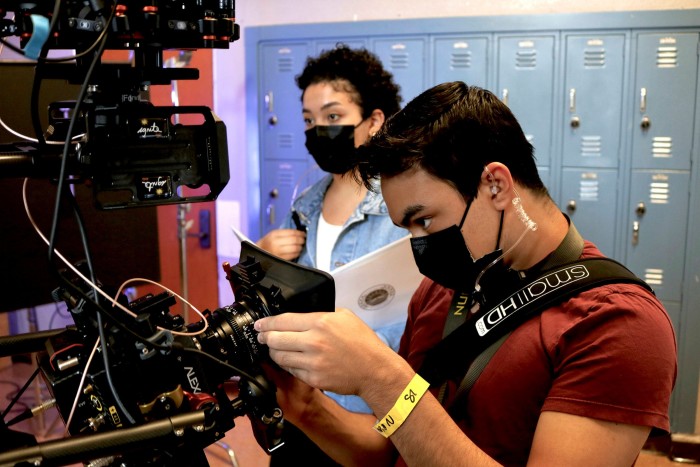

An exception is the Deutsche Bank Frieze Los Angeles Film Award: a main prize worth $10,000 and an audience award with a $2,500 prize, voted for by the public. Now in its second year, its goal is simple — to identify and champion emerging LA filmmakers. The execution brings together an intriguing mix of outsize names from film and art. Frieze is co-organising the event, this year supported for the first time by parent company Endeavor, the behemoth agency, and Endeavor Content. Their partner is the acclaimed Ghetto Film School, experts in developing talent from under-represented communities who typically lack access to the film business.

Like Frieze, the school also has bases in London and New York. (The first site opened in the Bronx in 2000.) But LA is always its own city. This year’s awards reflect its complexities. In John Rizkallah’s Dear Mama, the main prize winner, a young Middle Eastern woman relocated to LA tells her mother of her faraway new home. Sorry for the Inconvenience — which Jane Chow won the audience award for — unfolds in a family-owned restaurant in the city’s Chinatown.

For Ghetto Film School, it was vital the awards reflect its ethos. The academy is a non-profit whose programmes — one for younger teenagers, the other for 18-35-year-olds — are free to students. “What makes us different is offering support to artists in the local community, who are trained at no cost and the highest level of rigour,” says strategy and partnership officer Sharese Bullock-Bailey.

Socially inclusive to its core, the school has forged relationships with heavyweight industry players before. But its mission has never been compromised, which takes judgment. When Frieze first approached the school with the idea for the prize, Bullock-Bailey describes a careful period of getting-to-know-you: “They wanted to engage with a world-class film school that had real industry chops. And to connect at an inclusive level.”

The programme for the film award chooses 10 emerging LA filmmakers from an open field of applicants. Ghetto Film School’s tutors and mentors then support them in completing a project. With prizes at stake, the process is competitive — as is the film industry. It is also designed to foster community between the film-makers.

This year, the heft of Endeavor became another factor. Dan Guando is the executive who brokered that involvement. An admirer of Ghetto Film School, he saw his company’s ambitions echoed in the outreach built into the award. “Even in our staffing,” he says, “we want to be less insular than the industry model of attending a certain film school, then becoming an assistant.” Endeavor “turbocharged” the programme with resources ranging from masterclasses with agency clients to high-end equipment. The influence of Frieze rewarded visual ambition; story-driven Guando encouraged strong narratives.

The results are films of stellar promise. In Rizkallah’s Dear Mama, while the unseen homeland of the heroine is never named, mentions of orange blossom and power cuts hint that it is Palestine. (Rizkallah is Palestinian-American.) But the film is rooted too in the reality and legend of LA. The woman at the heart of the story speeds down oceanside freeways, thrilling to a drive without checkpoints; she buys Mexican food on Vine Street and wanders Hollywood Boulevard past Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

Rizkallah folded his mother’s stories of Gaza into the film. “Those stories are the blueprint of who I am,” he says. Like all the films in the competition, Dear Mama was shot months before the 2021 Israeli-Palestinian crisis. “The timing was crazy. When people finally saw Dear Mama, they were asking ‘Wait, did you make it this week?’” Naturally, the attention the prize brings to his film-making excites Rizkallah. So, too, the spotlight his film puts on its subject. “I love knowing film can reach beyond a news story to show you the people it actually touches.”

Jane Chow’s Sorry for the Inconvenience is another portrait of the “real LA” at a real moment. With the city in the grip of the pandemic, the Chinatown restaurant that serves as the location has been converted to delivery only. But Chow also captures ordinary life charmingly going on. The teenage daughter of the restaurateurs prepares for a school Zoom performance of The Tempest; her mother dispatches fortune cookies.

For Chow, winning the audience prize was a welcome endorsement. Originally from Hong Kong — she is currently the only member of her family in the US — the support network of Chinatown has huge meaning for her. “It was having a hard time even before the pandemic because that part of LA is being harshly gentrified. So I wanted to show people Chinatown isn’t just a cultural destination. It’s a home.”

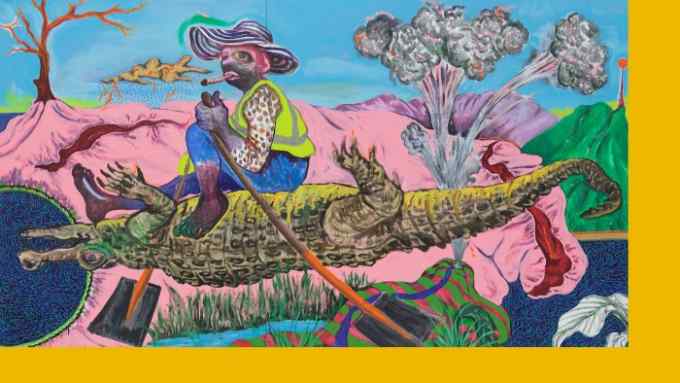

For Bullock-Bailey, the award cements a relationship between film and art that has always been closer than it looked. Ghetto Film School students have long been encouraged to compare, say, cinematography with a painter’s use of light. “We’re always thinking about those throughlines. We’ve been in shared territory [for] some time.”

The film-makers too feel comfortable at the junction of art and film. “There are so many parallels,” Chow says. “We’re both raising questions about this society we live in.”

Rizkallah makes another link — one connected in turn to his award. “Whether you’re a visual artist or a film-maker, you know your family is going to be mad at you because you’re going to live this life of struggle! So knowing there are organisations this major who want to support your work, I feel totally reignited by that.”

If art and film are adjacent, Guando says, so too are philanthropy and industry. “We want to help bring through voices who don’t have a voice. I’m also a selfish executive looking for film-makers. It’s hard for talent to reach big companies outside traditional routes, it’s hard for me to find them, and so many great voices are unrepresented and under-represented. So when I say selfish I’m joking — but am I talent-spotting? Absolutely.”

Comments