Will coronavirus break the UK?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This story is part of a major Financial Times series Coronavirus: could the world have been spared?, investigating the global response to the crisis and whether the disaster could have been averted.

It was a planeload of tourists returning from Greece that perhaps did most to expose the strain Covid-19 has put on the UK and the uneasy balance of power between its four nations. Sixteen of those flying into Cardiff airport on August 25 from Zante tested positive for coronavirus, forcing all 193 passengers to self-isolate.

For the Welsh government in Cardiff, the conclusion was clear-cut: Zante was a coronavirus hotspot and urgently needed to be added to the list of destinations requiring quarantine.

Vaughan Gething, the Welsh health minister, contacted UK government officials in London. Like Scotland, which had already imposed a quarantine on Greece, Wales had the right to impose its own public health measures but wanted to maintain a united front. This view was shared by Mark Drakeford, Wales’s first minister, who admitted to being “surprised” that London had left Wales the power to diverge on this. He had assumed the government would act under border security law rather than public health legislation.

“My view was that unless there was a very good reason why we feel we should depart from what the UK government was doing, we should stick with the decisions that they made,” says Mr Gething.

But what followed tested that theory to destruction. Delays, unanswered requests to central government and finally an incident that seemed to sum up the fraying edges of the four nations of the UK.

The crunch point for Mr Gething came on September 3. The British government did not see the need to quarantine travel from the whole of Greece and was still resisting the idea of quarantining individual regions. Before taking any decision, Mr Gething sent a letter with his arguments and agreed to wait for a meeting with the transport secretary that was arranged for 6pm that evening — but at 5pm the UK government announced it was keeping Greece off the quarantine list for England anyway. “We didn’t get a response to our letter,” Mr Gething recalls. “And then the UK made its decision an hour before we were due to meet.”

Enraged, surprised and baffled, Wales then acted unilaterally, adding Zante to its own quarantine list the next day. The following week the UK government followed suit for England.

The incident, trivial in the grand scheme of the crisis, showed how coronavirus had exposed the rising tensions within Britain, which, even before the pandemic struck, was already under strain from the fallout over Brexit. The virus has driven a greater wedge between the four nations of the UK, testing the boundaries of power.

PAST FRICTIONS

An uneasy settlement

The UK’s constitutional framework has been pieced together, picked apart and restitched over centuries. Northern Ireland’s parliament has existed since the partition of Ireland in 1921, although it has been opened and shut down throughout the region’s tumultuous history. In modern times, Wales and Scotland were, until 1998, essentially governed by British government departments under the control of a Westminster-appointed secretary of state.

This changed when the Scots and Welsh voted for former prime minister Tony Blair’s devolution plans. Both secured their own parliaments, first ministers and cabinets, along with substantial powers over domestic legislation, most significantly health. England, meanwhile, by far the largest and richest state of the union, has no legislature of its own, relying instead entirely on the Westminster parliament.

But while devolution visibly altered the daily lives of Scottish and Welsh citizens, creating different rules on everything from alcohol pricing to university fees, this was largely unnoticed in England. At the same time, in a political shift unanticipated by the Blair-era architects of devolution, the Labour party in Scotland collapsed, leaving the Scottish National party — a party that does not wish to be part of the UK at all — in control of government for the past 13 years. The four different governments are controlled by five different parties.

Even before the pandemic struck, the UK’s vote to leave the EU in 2016 had already set in train a looming constitutional crisis. Although Scots had narrowly rejected independence in 2014, Brexit, which they opposed by almost two to one, reignited the vision and polls now show a majority for separation.

The pandemic has highlighted the uneasy and unequal nature of the UK’s devolution settlement. It came as a particular shock to many in England, not least as the other first ministers began holding separate daily TV briefings. To his discomfort, Boris Johnson, the British prime minister, found that he not only had far less control over the UK’s levers of power, but also that he was forced to share decision-making with political opponents.

And the frictions were not limited to the devolved parliaments. Since 2000, nine of the great city-regions of England, including London, Greater Manchester, the West Midlands and Liverpool, have elected mayors with limited powers but a substantial mandate. They found themselves bypassed over decisions affecting their own regions.

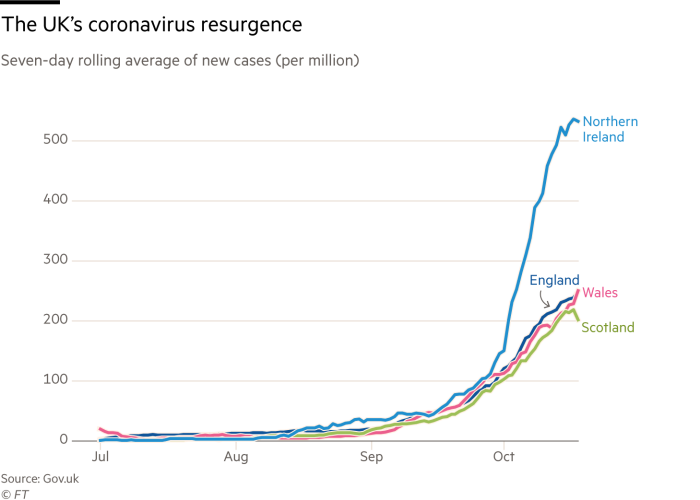

When the virus struck, it presented a unique challenge: a UK-wide crisis with no respect for borders but in an area where policy was not controlled from the centre. Over a series of interviews with key players, the Financial Times has pieced together the tensions and disputes that have left many in Westminster feeling that new institutions and methods are now needed if the union is to hold.

WORKING TOGETHER

First days of the crisis

Things started fairly smoothly. Mr Johnson’s government recognised the need for co-operation and the devolved leaders were also keen to work together. Insiders said there was no question of the Westminster government taking back powers for the crisis. In February, before the prime minister became actively involved, the UK’s emergency Civil Contingencies Committee meetings, or Cobra, led by health secretary Matt Hancock included the health ministers of the devolved nations together with the chief medical and scientific advisers.

The chief medical officers of the four nations have worked together well throughout. As the crisis grew, Nicola Sturgeon, the Scottish first minister, declared she “could not be less interested” in normal politics at that moment. There was, Mr Gething recalls, a “genuine attempt to get sign-off in areas of devolved responsibility”.

Mr Drakeford, an opponent of Welsh independence, was initially pleased as first ministers were invited to join the Cobra meetings. But it did not last: “Once the immediate crisis was over, that went into reverse,” he says. Furthermore, on too many occasions, from quarantine to track and trace to lockdown restrictions, it became apparent that Mr Johnson was not able to adjust to the reality that in a health crisis he was only the prime minister of England.

In a May 10 televised address laying out his plans for lockdown easing, Mr Johnson did not mention once that the measures only applied to England. Just hours earlier, Ms Sturgeon had appealed for “clarity of message”. “Decisions that are being taken for one nation only . . . should not be presented as if they apply UK-wide,” the first minister said.

Others were also unimpressed. In the first days of the crisis, much of the focus was on London, where the outbreak seemed to have hit hardest. Yet Sadiq Khan, the capital’s Labour mayor, was not invited to the UK’s emergency meetings until mid-March, even though the mayor is normally brought in whenever there are major incidents in London.

Yet when Mr Khan (the directly elected leader of a city with three times the population of Wales) asked to attend, his requests were initially declined. When finally he was invited, he discovered that crucial information was not being shared with him. “I got a phone call, I think on March 16, inviting me to a Cobra later that day, and that was the first time I discovered that the government had data [showing] London had double the number of Covid-19 cases as the rest of the country put together. But I wasn’t aware of the data the government clearly had.”

There are some defences available to the government. For a start, unlike the first ministers, the London mayor does not have health powers. Secondly, this was a fast-moving crisis and it was inevitable that not everything would run smoothly and (unlike other mayors) he was ultimately invited. While the British government accepted there were moments that could have been better, it put them down to the unique and all-consuming nature of the crisis.

But the failure to share crucial information left Mr Khan with a bitter taste. He was more surprised when, after the initial peak of the crisis, the Cobra meetings abruptly ended in mid-May. In Wales they were promised more contact by the prime minister, but Mr Gething says it never happened. Instead, they saw Michael Gove, the chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster responsible for liaison with the devolved governments. “We then got first minister meetings offered with Gove. But Boris Johnson did not re-engage.”

Some Conservative ministers meanwhile felt Ms Sturgeon was rushing to be first to announce measures that were already planned for England, in order to give the impression of more sure-footed leadership. They also believed Scotland’s leader was playing politics with the crisis, sheltering behind UK policy and the Treasury’s furlough scheme while using her own televised daily briefings to advance the nationalist agenda.

If it was, her strategy has paid off. An Ipsos Mori poll in May found that more than three quarters (78 per cent) of Scots thought their government had handled the crisis well compared with only a third (34 per cent) who said the same of the UK government.

In Wales, Mr Drakeford says that the handling of the pandemic, together with the bitter fight over sharing out new powers after Brexit, led to a seven-point jump in backing for independence, although support for it is still below a third.

HEADACHES AND CONFUSION

Appearance of unity crumbles

The charge of political profiteering is disputed by Ms Sturgeon’s allies. Humza Yousaf, the Scottish justice secretary, says: “For every other decision I have had to make you of course have to weigh up the politics, but on coronavirus the message from the first minister to all of us in the cabinet is that our ‘overarching, overriding and primary and only consideration’ should be public health. I just don’t even think about the question of whether or not this benefits, or doesn’t benefit, the cause of independence.”

Coronavirus: could the world have been spared?

The coronavirus pandemic has killed more than 1m people across the globe. But could it have been averted? A unique FT investigation examines what went wrong — and right — as Covid-19 spread across the world

Part 1: China and Covid-19: What went wrong in Wuhan

Part 2: The global crisis — in data

Part 3: Why coronavirus exposed Europe's weaknesses

Part 4: Will coronavirus break the UK?

Part 5: How New York’s mis-steps let Covid-19 overwhelm the US

Part 6: What Africa taught us about coronavirus, and other lessons the world has learnt

Finance is perhaps the thorniest area. Ms Sturgeon has complained that Scotland lacks the power to borrow on the scale needed to fund coronavirus economic support measures such as the UK’s furlough scheme. It is a complaint that taps into frustration shared across the devolved nations that decisions on economic support rest solely with the UK Treasury.

This brings hollow laughs in London, where they argue Scotland can take decisions to close down sectors, such as the hospitality industry, knowing the financial consequences must be borne by the UK Treasury. “We can be put in the bad corner for being ungenerous,” says a Conservative MP. In an intervention viewed favourably at Westminster, Arlene Foster, Northern Ireland’s first minister, has pushed for a threshold of infections that automatically ensures extra support from the Treasury if restrictions are imposed.

With the demise of the Cobra meetings, the first ministers were diverted into ad hoc calls with Mr Gove and bilateral calls. Mr Drakeford says: “They can be twice a week, and then three weeks without anything. When those meetings happen they are useful but you can’t run the United Kingdom entirely ad hoc and that’s what they are.”

For other observers, a problem increasingly was that the UK government wanted to take the decisions. “You could see that by the time they got to Cobra, there was often already a decision made by the Conservative cabinet,” says one regular participant.

During the lockdown phase from March, the four nations of the union worked in reasonable harmony, but Mr Johnson’s unilateral softening of the lockdown message in early May shattered the appearance of unity. Slogans proliferated across the four governments as their rules diverged.

Mr Drakeford feels it keenly: “Well, complexity of the messaging is an issue. A lot of people in our population are clustered along the border. We’re just the opposite of Scotland, where most people in Scotland live in the central belt. In Wales, the population is more densely to be found along our border, and many people in Wales get their news sources from English-based newspapers or broadcasters. So it’s always a problem for us, and it has been a frustration persuading the prime minister to be explicit about when he’s making announcements that apply to England, not the UK.”

Being explicit about the limits of his powers was not something Mr Johnson instinctively liked: “I don’t think he warms to that idea,” says Mr Drakeford. “And that leaves people having to come and mop up behind, making it clear to people, well, ‘actually that doesn’t apply in Wales’, or ‘actually, no, that does apply’.” The headaches caused by these confusions were neatly captured in May when Wales still had a five-mile limit on travel and England had lifted its own. Welsh police officers escorted a furious English woman off a beach in Barmouth, north-west Wales, almost 100 miles from her home. When they explained Welsh lockdown rules she indignantly retorted that she was within her rights to be there because “Boris Johnson said that you can”.

Another example that infuriated Cardiff was the shift in the summer that led to testing being opened up, initially to almost anyone who wished to get one. “So, to us, [there was] a sudden announcement that there were going to be 100,000 tests available. And at that point the message that appeared to be being given was, ‘anybody who wants a test should line up and have one. Send us your huddled masses.’ So, we hear it first on the radio,” says Mr Drakeford. “Our message in Wales has always been that testing is important, but it has to be testing for a purpose.”

Scottish ministers say some of the problems stem from simple unawareness of the extent of devolution among UK ministers, citing as an example the system for quarantining travellers, which was introduced in chaotic fashion in early July.

“I think there were some in the UK government that thought that because this involved international borders, it was a decision wholly for the UK,” says Mr Yousaf. In fact, the devolved powers over public health and policing would be central to any enforcement. But UK ministers were surprised when Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland declined to endorse automatically the Westminster government’s quarantine list. Mr Yousaf adds: “I think it was genuinely mostly coming from ignorance . . . I don’t think there was anything particularly malicious about it.”

Still, Mr Yousaf says co-operation has improved markedly on quarantine since, with the UK government arranging better access to data from its Joint Biosecurity Centre for making quarantine decisions, although he adds: “I still get frustrated by the fact that I tend to hear about what the UK government’s plans are via the Daily Telegraph the day before we have our joint ministerial meetings.”

The london factor

Lockdown split

The frictions visible between the constituent nations of the UK were equally visible within England itself, where the pandemic asked questions of piecemeal governance structures. As mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham has more powers even than Mr Khan but has not been invited to Cobra meetings at all, even though he is a former Labour health secretary.

As political pressure built in Westminster to reopen the economy in mid-May, Mr Burnham was clear that in the north, where the virus was still only just past its peak, it was still too early to come out of lockdown. He was ignored, he says, and found out that the national restrictions were being eased only when local health officials picked up that the government was planning to shift its slogan from “Stay at Home” to “‘Stay Alert”. “I can remember feeling astonished that it happened. I just couldn’t believe it the day when it was first put to us without consultation,” Mr Burnham recalls. “I think the voice of London business was heard because they were saying, ‘oh, look, the cases are low, we need to get back’. It wasn’t the same for us at that moment; very centralising, very much hearing ‘London first’.” The current surge of cases in Manchester, Liverpool and other areas of the north looks to have vindicated Mr Burnham’s concerns that the “unlock” came far too early for them, a move for which the region is now paying a disproportionately heavy price.

For those in the devolved nations and major regions, it frequently felt like Mr Johnson’s government was struggling to adjust to the more federal nature of the country that was being exposed daily by the pandemic. One former Downing Street official observes that there is “an almost colonial mindset” among some ministers and officials, especially in those departments less used to the devolved structure. Often the mistakes are due to London ministers forgetting this.

The “colonial” mindset can have serious consequences. In early September, Mr Gething was shocked to find that testing capacity was being cut in areas such as Rhondda and Caerphilly, where the incidence of the virus was still high. The decision was made as the UK suddenly found itself struggling to cope with an upsurge in demand for tests, forcing lab capacity to be switched to areas of greatest need. It meant that many hundreds of tests previously available in high-incidence areas would now be reduced to 60. “They did it [made the decision based] on a report from the Joint Biosecurity Centre that had only English data,” Mr Gething recalls. Mr Hancock responded quickly “but it illustrated a wider problem”.

Mr Burnham, as a former cabinet minister, understands the centralising bent of Westminster and Whitehall but believes the pandemic had made the case for a greater decoupling of local policy and divisive national party politics. He contrasts the comparative success of Germany and its federal structure in responding to the virus. “Westminster sees everything through the divisive prism of party, whereas we as mayors start with place, not with party,” he says.

There are signs the government is trying to learn from its mistakes. In May it recruited Tom Riordan, the chief executive of Leeds city council, to help bridge the gap between the national test and trace system and local councils, which are responsible for tackling large outbreaks. On the powers of metro mayors, Mr Gove says this is still a “work in progress”.

CALLS FOR REFORM

‘A learning process’

Why did coronavirus expose such fissures? The simple answer is that it was a nationwide crisis that defied borders in an area where power had been devolved. But it also came at a time when the existing settlement was under strain. The question for many is whether the UK government can adapt to the realities of a federal, or at least semi-federal, structure. The absence of an English parliament means English politicians think differently about the powers of Westminster. Yet an English parliament would create many new problems, given the nation’s overpowering size and wealth compared with the rest of the UK. And yet there is no forum that gives the mayors a powerful voice in England.

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT's live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

Again, the Welsh position is noteworthy, as its government is still unionist. Mr Drakeford is clear that the crisis has shown the British government needs to change its mindset and its structural mechanisms.

Mr Gove agrees that some institutions need reform. “It has been a learning process for everyone. It does raise a broader question, not about power grabs and clawbacks but making sure the whole devolution settlement works.” He is now accelerating a slow-moving review into intergovernmental structures, which he says will put the relationship on a “firmer basis”.

While he feels the four nations work together fairly well, he recognises that communications could be improved: “I think that from our point of view we should have always and should continue to involve them in more conversations. The more trust that is shown in a crisis, the less likely it is that friction, confusion and misunderstandings occur.”

Welsh and Scottish leaders want to see meetings of first ministers and the prime minister put on to a more regular, scheduled, footing. Mr Gove agrees and promises more regular meetings both for first ministers and for secretaries of state with their devolved opposite numbers where all can put items on the agenda. “Could we have had them more regularly over the summer, yes. Have some been haphazard or ad hoc, yes. Was that a deliberate effort on our part to disengage? No,” he adds.

The danger is that this sounds dangerously like lip-service to Scottish and Welsh ears. Both governments were staggered by the recent publication of the UK government’s internal markets bill, setting out the post-Brexit dispensation for the UK economy, which they argue was drawn up without any respect for managing divergence between the nations. Ms Sturgeon called it “an abomination” and the Welsh government said it was “an attack on democracy and an affront to the people of Wales”.

More radical are calls for a form of qualified majority voting on matters affecting all of the UK so that the British government would need the support of at least one of the other three nations for a measure to go forward. Mr Gove disagrees, saying it would “impede decision making”. Ministers note that there are many examples where the UK government agrees to ideas put forward by the other nations, one example being the demand for self-isolation payments. Even on quarantine, where Tories accept there was “some bumpiness”, they note that the same arguments are happening within the UK government and that, for all the differences, the problems had been around specifics, not principle.

David Lidington, Mr Gove’s predecessor and the de facto deputy prime minister under Theresa May, says the fundamental obstacle is something no British government looks likely to wish to change. “The obvious straitjacket is Westminster’s voting system. If you have a majoritarian system at Westminster, and Westminster is sovereign, then whatever is put in place, it is always trumped by Westminster being sovereign. As a result, any solution will have a sense of impermanency.” Unlike a number of European nations, and indeed the devolved parliaments, Westminster’s leaders are used to supreme power and not to cross-party collaboration.

More troubling for the first ministers is that while Mr Johnson’s government talks of decentralisation, there are those around him who wonder if too much power has already been surrendered. What discussions there are around devolution do not yet suggest a major overhaul.

Mr Drakeford is concerned: “I do think that for some Conservative political figures, coronavirus has demonstrated to them the dreadful mistake that was made in allowing devolution in the first place. And these are people who’ve never had to bother themselves much about it, and now that they discover it, they’re horrified. So, I think, there are undoubtedly people who come away from this experience thinking that what is necessary is to clip the wings of devolved administrations and to reassert the authority of the UK government.”

Mr Gove disputes this. “It has been a difficult and strange time but from it we’ve learned lessons about all sorts of things, about what works and doesn’t work in government. It has also exposed some of the strengths and weaknesses of how the union works. Devolution can work effectively but, like all relationships, it requires constant attention and in the past there was a slight devolve-and-forget approach [from all previous UK governments]. What we have got to do is not try to dilute devolution but make it work better, and it works better by being in a state of constant repair and renovation.”

Just as the virus has been most deadly to those with underlying health issues, the crisis has homed in on frailties in the UK’s institutions, pulling at the seams of the union. The question still to be answered is whether an overhaul can deliver a leaner, fitter and still whole United Kingdom or whether Covid-19 has highlighted fundamental comorbidities in the nation’s body politic.

Join the conversation

How has the pandemic been handled where you live? What has gone right or wrong for you during this time? Do you work in a sector that was hit hard by lockdowns? Or have you managed to adapt your life positively? Share your experiences in the comments below.

Additional reporting Sarah Neville, Bethan Staton and Robert Wright

Letter in response to this article:

Comments