Sotheby’s sale focuses on postwar British abstract art

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Critical reputation is a curious thing. Artists can find their critical fortunes fluctuating wildly during their lifetimes; whole “schools” of art can be overlooked or marginalised. This has been the peculiar fate of much British art, which has tended – not always unreasonably – to be cast to the outer margins of art history. That changed dramatically at the end of the 1980s when the YBAs exploded into the international vanguard – but to imagine that earlier British artists were working in a kind of parochial cultural vacuum could not be further from the truth.

It was not always easy, however, for British artists to keep abreast of developments overseas. Immediately after the second world war, for instance, when New York began to rival Paris as the centre of “modern” art, Britain was bankrupt, rationing was still in force and foreign travel, even if you could afford it, was constrained by currency restrictions. Specialist art publications (illustrated in black and white) were rare, few public institutions addressed contemporary art and only a handful of commercial galleries exhibited the work of foreign artists.

Despite all this, British artists did engage with the international avant-garde. The fruitfulness of the dialogue between the abstract painters working in postwar Britain and New York, in particular, is the focus of a sale of some 20 British paintings and drawings on offer at Sotheby’s London on December 10. Including just five artists linked with the artists’ colony at St Ives – Alan Davie, Roger Hilton, Peter Lanyon, Patrick Heron and William Scott – and drawn from the exceptional holdings of the Canadian media magnate David Thomson (the third Lord Thomson of Fleet), it represents the finest group of postwar British art to come to the market since that amassed by another collector of genius, the anglophile American Stanley Seeger, in 2001.

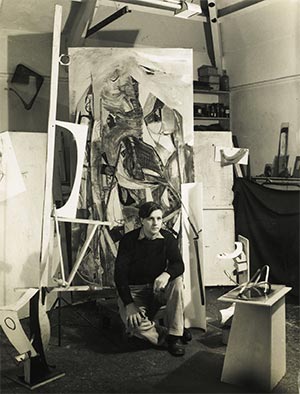

Sotheby’s is working hard for the sale, which is simply entitled Abstraction, with a New York preview and illuminating catalogue essays including James Rawlin on the Anglo-American dialogue and Simon Hucker on William Scott’s friendship with Mark Rothko. The transatlantic links are underlined by evocative grainy photographs: Rothko with Scott in Somerset, and with Terry Frost and Peter Lanyon in Cornwall; Heron with the legendary critic Clement Greenberg; Scott on the East Hampton porch of the no-less-seminal dealers Leo and Ileana Castelli, in front of a half-finished de Kooning; and an installation of a show of Hepworth, Scott and Bacon at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York.

The reason for this focus is straightforward. British postwar art in general, and British abstraction in particular, remains hugely undervalued in relation to its European and US counterparts.

Henry Moore and Francis Bacon have made the transition to the big-buck mainstream postwar auctions, but few others. As the Modern British art dealer James Holland-Hibbert puts it: “There seems to be a stigma about British art, as if it were not relevant to the rest of the world. For me, Peter Lanyon is the best of this group, and a great Lanyon is as good as anything by any of his international contemporaries.”

To put all this in a market context, only Nicholson, Heron and Scott among postwar British abstract painters have fetched more than £1m at auction, and none has quite made it to £2m.

“There has been a gradual but marked renewal of interest in these artists,” Thomson says, “but there is still a way to go to reach the level of deserved appreciation and renown, and this sale has the potential to highlight their significance.

“In terms of letting go of the works,” he adds, “a collection needs to evolve. Articulation or refinement transpires over years of communion with the objects. The process is always hard fought.”

Thomson began acquiring works by these artists in depth in the late 1980s, attracted to their “expressive power and inherent sensibility towards light and atmosphere”. These qualities are particularly apparent in arguably the most substantial of the trimmings from his collection, Heron’s “Atmospheric Strata: February 1958” (estimate £300,000-£500,000).

These colour-stripe canvases reflect the intensity of colour and light experienced in Heron’s garden above the rugged Cornish coast. The artist explained: “The reason why the stripes sufficed, as the formal vehicle of the colour, was precisely that they were so very uncomplicated as shapes. I realised that the emptier the general format was, the more exclusive the concentration upon the experience of colour itself.” The work also illuminates the essential difference between his colour-field paintings and those of Rothko. Herons are not about emotion but colour itself.

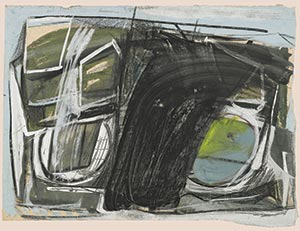

Heron recorded in 1956 how he felt “elated by the size, energy, economy and inventive daring” of new American paintings: “Their creative emptiness represented a radical discovery, I felt, as did their flatness, or rather their spatial shallowness.” In contrast, Hilton, whose bold “August 1953” (£50,000-£70,000) similarly derives from the rhythms and hues of nature, remained resolutely Francophile in his leanings. He was the only one of the five not to have had solo shows in New York, or to see his work so widely represented in North American museum collections.

It could be argued that, for all their affinities with their US and European counterparts, these five artists are most striking for forging their own pictorial language. It will be interesting to see what Americans make of it now.

Comments