John McAslan, master of the architectural intervention, is taking on Penn Station

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Architect John McAslan stands in Glasgow’s The Burrell Collection. A slice of modernism, completed in 1983, it houses one of Scotland’s finest art collections: some 9,000 artefacts amassed over a lifetime by Sir William Burrell and Constance, Lady Burrell. The museum, which was formally opened by King Charles last month (although it has been welcoming the public since March), has been preserved and revitalised in a £68.25mn revamp under McAslan’s guidance. For McAslan, who was born in the city, “it’s a way of giving back”.

Inside the museum, among the swish of Degas’ Red Ballet Skirts and the silhouette of Rodin’s The Thinker, McAslan is drawn to the Warwick Vase, a Roman marble endowed with new life through partial restoration. The vessel could be a symbol for his own work: repair and renewal have become a speciality of his practice John McAslan + Partners alongside its shiny new developments. “Not everyone likes The Burrell but the renovation budget was around a fifth of the cost of an equivalent new-build museum, and environmentally speaking it will now be around for another 50 to 60 years, maybe longer,” says McAslan of his approach, which is led by a commitment to sustainability as much as aesthetic improvement. “I find it enriching to work with what exists: the layers of history and the community connections. But I’m not into faithfully restoring a Palladian villa because there would be no opportunity to intervene. It’s the architectural interventions that I enjoy – taking something that is broken and fixing it.”

McAslan, 68, is an architect you may not have heard of, but you will be more than familiar with his work. His firm led the restoration and extension of the historic King’s Cross Station. He was also one of the collaborators, alongside engineering services firm WSP, responsible for the new Bond Street station that connects the Elizabeth Line. His practice, which has outposts in London, Edinburgh, Belfast and Sydney (with a new studio opening shortly in New York City), has received more than 200 international design awards, and in 2012 McAslan was appointed a CBE for his services to architecture.

By 2024, those riding the subway in Sydney will likely pass through one of McAslan’s team’s next triumphs: the A$1bn (around £555mn) transformation of its historic Central Station, Australia’s busiest transport hub, delivering new Sydney Metro platforms and concourses beneath the station and a new hall encompassing its historic buildings. The project is being built by Laing O’Rourke with John McAslan + Partners and Sydney-based Woods Baggot.

The firm is also part of the estimated $7bn upgrade of New York’s Penn Station. Last year, commuters were consulted on two options for improving Penn Station following the 1963 demolition of the grand beaux-arts building at ground level. The preferred option is for a single-level space focused on a grand train hall with a 140m-long atrium between Madison Square Garden and 2 Pennsylvania Plaza, which led to the recent approval of a one-year base contract (worth up to $57.9mn) to develop a preliminary station design to a joint venture led by FXCollaborative and WSP USA engineers with John McAslan + Partners as collaborating architect.

“Can you imagine? It’s one of the busiest transport facilities in the western hemisphere, linking up 600,000 passengers a day, and is unbelievably complicated as it’s beneath Madison Square Garden,” says McAslan of the enormity of the project, expected to unfold over the next four to five years. “It is a once-in-a-lifetime cultural project; hundreds of millions of people will pass through it every year; and if we can make it better, that is some achievement.”

Station to station

McAslan, a polymath as much inclined to talk about art as architecture, defers the plaudits to his team and their collaborators. He prefers to chat informally about his work through his favourite books and the architectural models displayed in a gallery-like space back at his London offices. We stand before a miniature King’s Cross, its vortex-like extension creating the station’s jaw-dropping western concourse. “What was important at King’s Cross was preserving the fabric of the Grade I-listed building,” says McAslan. “I remember walking around there with [the late] artist Terry Frost, who was a great guy, and I had this idea that it should be a double rainbow with a pull-out train shape. He said, ‘Oh, I like that. It’s a happy station,’ which he interpreted as a drawing.”

The challenges of building his happy station were numerous, not least as his extension, engineered by Arup, took science into sorcery. “There’s no intervention at King’s Cross. Nothing is damaged because essentially the extension is a freestanding structure, which didn’t require support,” he says. “And when it was finally finished – thousands and thousands of pounds later – the frame was put in place, sank about six inches, and then it spread about six inches before it finally settled. Only then did the engineers fine-tune and stiffen the structure. They are true geniuses. It is so beautiful to think a building could behave that way.”

He sees beauty in all buildings: the practice has worked on projects as diverse as the Mandarin Oriental Hotel and Residences in Qatar to contemporary residential tower blocks and mosques and museums including Doha’s sleek Msheireb Museums. It is a far cry from Dunoon, the sleepy Scottish enclave in which McAslan was raised, which was awakened in 1961 by the arrival of the Americans in nearby Holy Loch, who established a submarine base there during the cold war. The blow-ins opened the young boy’s eyes to horizons beyond heather-fringed borders. “Suddenly we were at the centre of the world, as Polaris missiles pointed between Moscow and Scotland,” he recalls. “The Americans brought all this stuff like Mad magazine and a fascinating diverse culture, which hugely influenced me.”

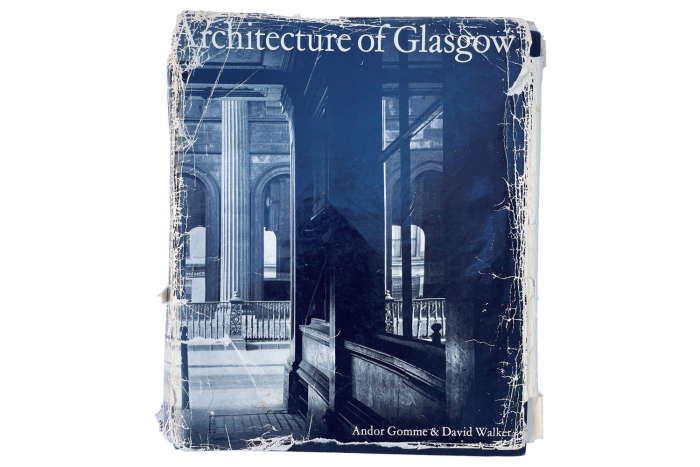

This brush with Americana fused with the excitement of visiting Glasgow city. “I was a fan of Queen’s Park FC, they were amateurs then, with the motto ‘To Play for the Sake of Playing,’” he says. The city provided further inspiration. He picks up a copy of Architecture of Glasgow, its edges frayed with thumbing. “This is the first architecture book I bought in 1968. Glasgow’s architecture is just phenomenal, as was Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, a pioneer who may well have influenced the early work of Frank Lloyd Wright,” he says, flicking through its pages. “It’s funny, the backs of the buildings are often more interesting [in Glasgow] because while the fronts are neo-classical, they have a kind of stripped modernism, almost like an early Bauhaus building.”

McAslan also points to similarities between parts of Glasgow and American cities like Buffalo, Philadelphia and New York – synergies that struck him long ago when his father left Scotland and moved to Baltimore. “I travelled a lot then and became really interested in the architecture just by seeing the country from Greyhound buses,” he recalls. His experiences led him to enrol in architecture at the University of Edinburgh, where he obtained an MA in 1977 and Diploma in 1978, along with the Diploma year prize. But he “soon felt claustrophobic”. The call of America lured him, and for a time he trained in Boston with CambridgeSeven.

Then came a chance encounter with Richard Rogers and John Young, who offered him a job back in the UK. The year was 1980. “It was a magical time. Richard was a fantastic guy, as was John, a phenomenal technical architect who did these wonderful drawings for Lloyds before retiring.” Four years later, having got the itch to go it alone, he co-founded Troughton McAslan, before establishing John McAslan + Partners in 1993.

His work has since taken him all over the world, as seen through the architectural models encased in perspex boxes around us: the cylindrical form of London’s Roundhouse sits on one shelf, a Grade II*-listed former steam-engine structure preserved in the midst of its transformation into a performance venue in 2006. The domed towers of Haiti’s Iron Market at Port-au-Prince rise from another podium, the structure restored after the devastating 2010 earthquake. One model in particular catches the eye – its internal workings represented as a series of handmade silver tunnels. It turns out to be part of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Florida Southern College.

“It’s the Polk County Science Building, one of his last buildings. It was falling apart and was going to be demolished when I discovered it,” says McAslan. “I thought, I have to save this, but the only way to do that was to dig tunnels through the building to service the horrendous combination of wet and dry labs, which were absolutely lethal. You could have grown monster figures inside there because of the cross contamination. It was a major intervention – but it was a building that was going to be lost forever otherwise.”

Many of McAslan’s pet projects have led to his involvement in fundraising – work that often pulls him away from the mainstay practice but which he finds the most rewarding. He and his wife Dava Sagenkahn got together with locals in Dunoon in 2008, setting up a preservation trust and raising £3.5mn to restore Dunoon Burgh Hall, now a thriving creative hub, and McAslan is hatching a plan to lobby the Greater London Authority on social housing and the mandatory provision of homeless shelters in new-build developments. Close to his heart, however, is his practice’s zero-energy classroom buildings for rural schoolchildren in Malawi (with Arup), which came about through ex-president Bill Clinton’s Clinton Global Initiative in 2010. “They provide a safer environment with better light and air and teaching conditions than the typical school buildings that were being built, but at the same cost at $25,000 per classroom building,” McAslan says of the concept. “But the real beauty is that in many cases the mums can stand and look in through the classroom windows, so they are also taught to read and write.”

New projects include his participation in two UK buildings: the dark-timber-clad £64mn British Museum Archaeological Research Collection, set to open in Berkshire in 2023, and a new £75mn low-energy archive for The National Galleries of Scotland. “It’s part of the waterfront regeneration, so the kind of project I really like – making places work better,” McAslan concludes.

Comments