Tighter emission standards for ships propel energy savings at sea

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When the biggest container ships ever built leave the Jiangnan shipyard near Shanghai next year, they will demonstrate the shipping industry’s slow chugging towards a low-carbon economy.

Able to carry up to 22,000 twenty-foot long containers, they will be propelled by vast tanks of liquefied natural gas instead of depending on the heavy fuel oil that has powered most vessels for the past 100 years.

The order by France’s CMA CGM is partly the result of pressure on shipping companies to cut greenhouse gas emissions that now account for about 3 per cent of the world’s total.

Vessels powered by gas emit up to 20 per cent less carbon dioxide per unit of energy than traditional ships, according to DNV GL, a body that oversees ship standards. “I think in the long run shipping and aircraft are the only things that need large quantities of energy-dense liquid fuels,” says Gerd-Michael Würsig, the organisation’s business director for LNG ships. Mr Würsig predicts that those fuels may in future be produced by synthetic methods, rather than drilling. But he goes on: “Shipping and aircraft will run on hydrocarbons even in 200 years.”

Yet the most urgent pressure on shipping companies’ fuel use stems not from concerns about climate change blamed on the consumption of fossil fuels but curbs from 2020 on sulphur emissions associated with respiratory disease and acid rain.

The rules effectively ban shipping companies from using the industry’s traditional “bunker” or heavy fuel oil, a byproduct of the refining process. The regulations should also boost interest in fuel-saving technologies including more efficient propellers. Less carbon-intensive LNG also meets the sulphur requirements. “These things should become more attractive because of the high fuel price,” Mr Würsig says. “This will lead to an increased efficiency in the ships overall.”

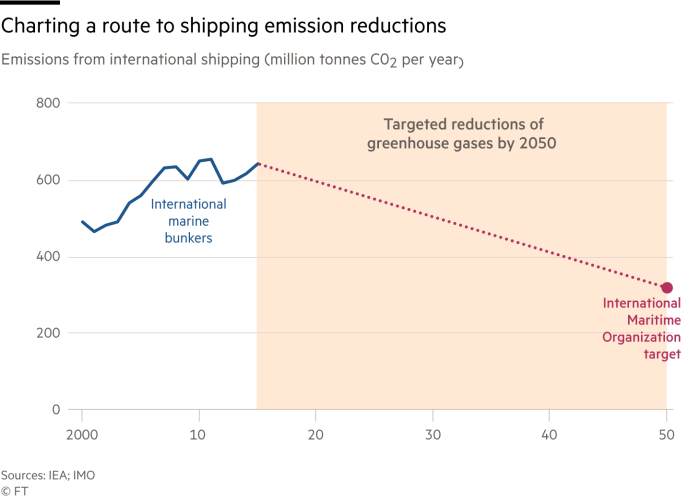

The industry is also set to face direct challenges over its greenhouse gas emissions. International Maritime Organisation rules demand that ship designs become 30 per cent more fuel-efficient by 2025 than the average for 2000-10. The UN body has also set targets to cut the industry’s carbon dioxide emissions per tonne-mile — a measure of the amount carried and the distance travelled — by 40 per cent by 2030 and by 70 per cent by 2050.

To ensure that the improvements are not cancelled out by increases in traffic, the industry also undertook to reduce its overall carbon dioxide emissions by 50 per cent by 2050.

Promising design changes for the future include new compressed air systems that will generate streams of bubbles over vessels’ hulls to reduce the energy needed to propel them. Some changes are very simple — to do with cleaning and painting of ships’ hulls or operating at slower speeds.

Nevertheless, the debate over the source of power remains central.

Tim Kent, technical director for marine at Lloyd’s Register, the London-based classification society, sees a future role for batteries in powering ships, with that technology “advancing all the time”.

Mr Würsig accepts there is a role in shipping for hybrid technology similar to that envisaged for vehicles. On-board batteries on vessels including passenger ferries can provide extra power when needed. The engines can then recharge the batteries during the voyage before arrival at the next port. The system can ensure the engines are constantly operating at optimum speed, rather than revving up and slowing down.

Yet much of the DNV GL’s research remains focused on systems designed to squeeze more efficient, cleaner power out of hydrocarbons. Among them is a design for a container ship that would use gas turbines powered by LNG to produce electric power to drive a highly efficient set of propellers. The technology differs from CMA CGM’s new ships, which will use LNG in a traditional, two-stroke internal combustion engine.

According to Mr Kent, only the growing use of batteries — charged perhaps by onboard, fuel-burning engines or even charged up at shore in the same way vessels currently take on bunker fuel — will meet the needs of the future. “When I think of the challenge that the industry has to reduce its carbon footprint, radical changes in the technology are going to be required,” he says. “I really think that’s the case.”

This article has been amended to clarify remarks by Gerd-Michael Würsig

Comments