Robert Smithson — land art’s alluring pioneer

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

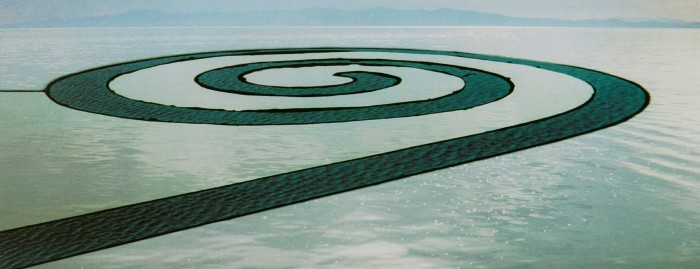

Towards the end of the film Robert Smithson made about the construction of “Spiral Jetty”, an earthwork at Rozel Point, Utah, we see the artist running its 1,500ft length. As the waters of Utah’s Great Salt Lake dissolve in splinters of sunlight, Smithson cuts a lithe, long-legged figure, his floppy dark hair and snow-white shirt intensifying his youthful vitality as he trots along the curling path he has constructed from basalt, mud and salt crystals jutting out from the shore.

Three years later, the artist was dead. Just 35 years old, he was killed in a plane crash while photographing another of his works, “Amarillo Ramp”, in Texas. His death was a tragedy both for his loved ones and for the wider arts community who shared a growing awareness that Smithson was set to be a titan of 20th-century art.

“I think all artists think they are immortal,” observes the British artist Tacita Dean when I ask her for her feelings about Smithson’s early death. “To die trying to film one of his works, it’s just absolutely . . . ” That the contemporary artist and film-maker, a colossus in her own right, cannot finish the sentence illustrates just how cruelly his loss has been felt by subsequent generations.

Yet Dean also observes that Smithson’s untimely passing rescued him from the trap which menaces genius as it ages. “It means you don’t go off-piste . . . get frayed by life, compromise.”

Certainly, Smithson side-stepped this fate. Born in New Jersey in 1938, he produced work that is held in major institutions including the Whitney Museum and MoMA in New York and Tate Modern in London. Considered a founder of the land art movement which encompassed talents such as Richard Long, Walter De Maria and Ana Mendieta, Smithson — as Dean’s words testify — has influenced many of today’s leading contemporary artists in a manner few of his peers can rival.

Now he is the subject of two new shows in Europe as the Marian Goodman Gallery inaugurates exhibitions devoted to him: Hypothetical Islands in London and another, Primordial Beginnings, in Paris.

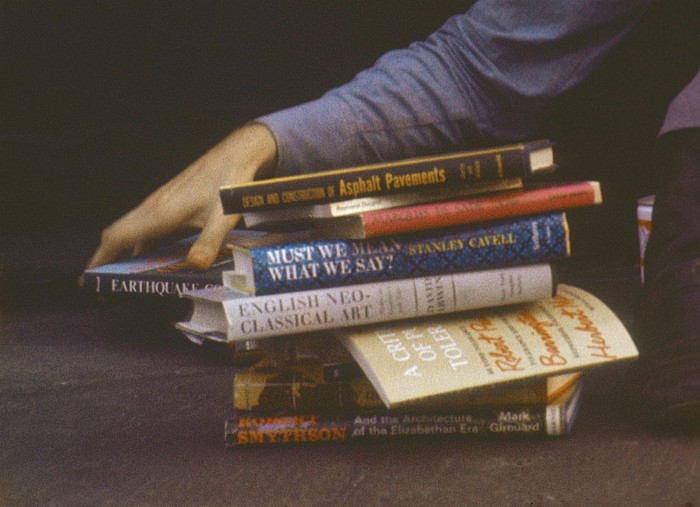

The London show focuses on Smithson’s interest in islands. It features more than 50 works made from 1961 to 1973, including two previously unseen films by Smithson’s wife Nancy Holt, with whom he often collaborated — “Bob with Books” and “Mangrove Ring” (both 1971). The Paris show meanwhile gathers works on paper that illustrate his fascination with the origins of the world.

Both shows must rise to the challenge of capturing an artist who refused to kow-tow to the authority of institutional displays. He was dismissive of much contemporary art — in a text on an exhibition at New York’s Armory, he lamented “the nullity of art” and opined “the greater the emptiness, the grander the art”. He referred to the works he put in museums — drawings, maps and films that related to his pieces of land art — as “non-sites”, as a way of distinguishing them from the earthworks, which he deliberately built in obscure, deserted and often intractable locations.

“He was interested in the intangible space between here and elsewhere,” says Lisa Le Feuvre, director of the Holt/Smithson Foundation. “He was asking: what does it mean when you physically bring the elsewhere to the near? That ‘elsewhere’ is a leap of the imagination. His work is so many things: it’s not just the thing, it’s the journey there, the imagined spiral jetty, the photographs, the rumours.”

Her words echo the experience of Dean. “When I was at art school like every kid of my generation, we would see [an image of] the Spiral Jetty,” she recalls. “And we had no other concept of it, really.”

Dean decided to see the work for herself, embarking on a complicated “pilgrimage” to Utah at a time when “America was a much more mysterious place than it has become”. But when she arrived, the jetty had sunk under the water’s surface. “So the first time I went there, I never saw it,” says Dean. “And because I never saw it became much bigger in my soul.” In 1998 she made an audio work, “Trying to Find the Spiral Jetty”, about the experience.

Smithson, surely, would applaud such a response. His 35-minute, 16mm film “Spiral Jetty” — which documents the construction of the earthwork and will be on show in a digitised version in London — is less a chronicle of a building project than a visual poem whose stanzas flit from the churning maw of a bulldozer through the lap of water on salt crystals, and ethereal images of dinosaur skeletons in museum vitrines. Every now and then Smithson recites map co-ordinates, or a list of natural materials from which the earthwork is made. The effect is to drill into deep time, reducing the industrial era to a moment that is ancient but fragile and fleeting.

Little wonder that Dean, an artist whose fidelity to analog film has made her the praise-singer for a disappearing world, claims Smithson as a “comrade” and says she experiences “a sort of jouissance” in sharing with him “a sense of atavism, of going back to ancestral prehistory, of thinking about time in terms of the journey into the earth, not just this linear, diaristic thing, but a sense of old land”.

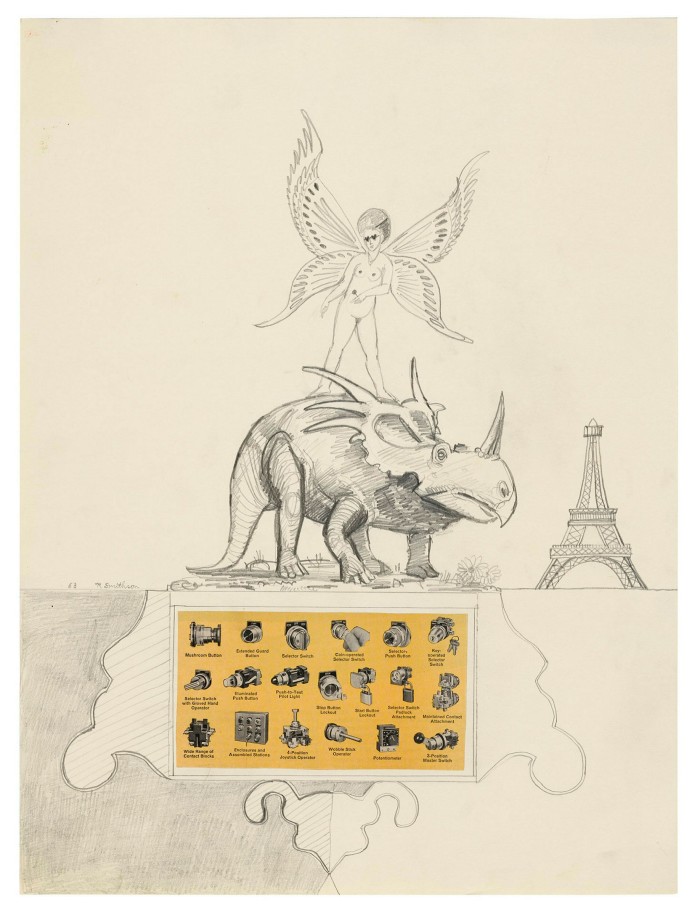

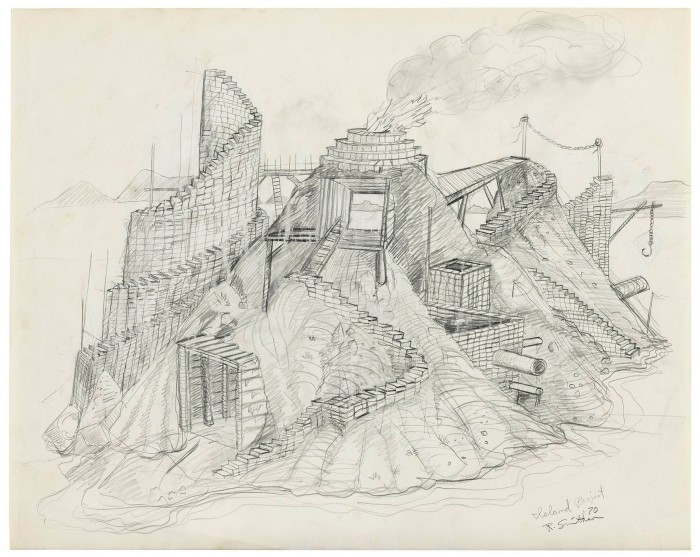

Smithson’s fascination with what he described as “origins and primordial beginnings . . . the archetypal nature of things” will be explored in the Paris exhibition. It will include rarely seen works on paper from 1961 in which wavy lines, intricate patterns and black holes suggest primordial landscapes. Further drawings and collages from the early 1960s experiment with images of turtles, dinosaurs and amphibians sometimes juxtaposed with human figures as if re-stitching us into our ancestry.

Not that Smithson fell prey to nostalgia. “He was controversial because he observed that we couldn’t turn back the clock. He saw artists as geological agents that could mediate between ecology and industry. He wanted to make collaborations with mining companies,” Le Feuvre says, referring to projects such as the “Bingham Canyon Reclamation” plan. Never realised, its aim was to reimagine the world’s largest open-pit mine, in Utah, as a work of land art. The Kennecott Copper Corporation had not responded to the request by the time of Smithson’s death.

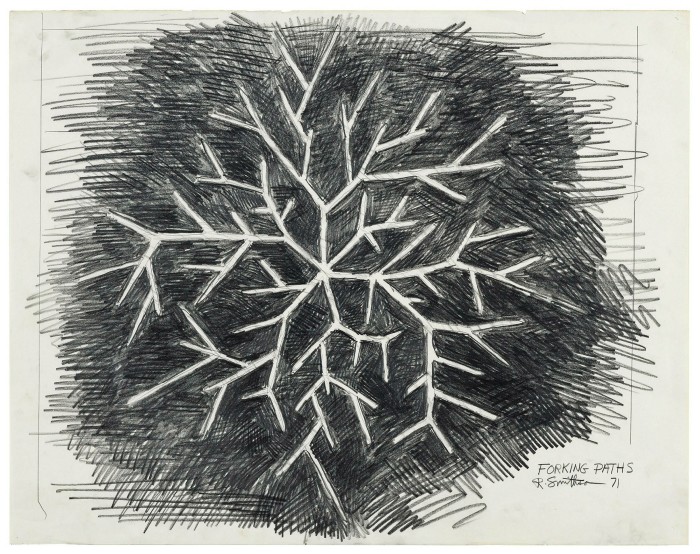

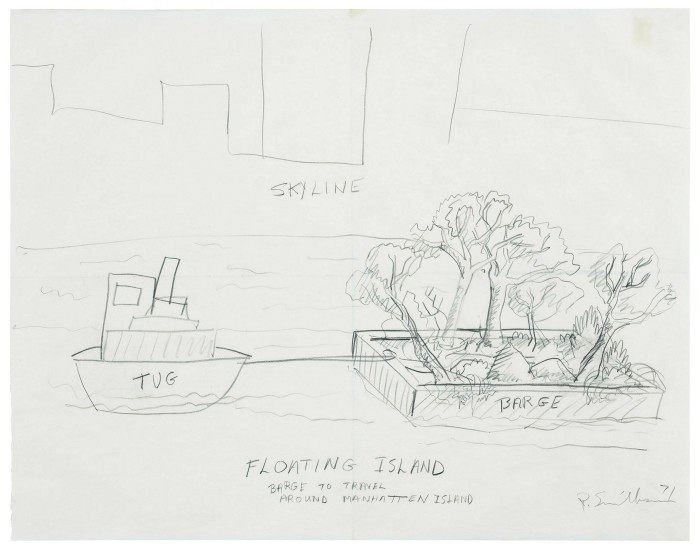

Smithson’s captivation with the mechanised actors of 20th-century progress is evident in pencil sketches on show in London such as “Floating Island - Barge to Travel around Manhattan Island” (1971), which shows a tugboat towing a barge planted with trees. Never achieved in Smithson’s lifetime, the project was realised for a week in September 2005 in collaboration with the Whitney Museum.

Was Smithson an early eco-warrior? Or complicit in the landscape’s devastation? Le Feuvre says he was “cognisant that industry had scarred the landscape and we could not go back. He wanted to demonstrate that . . . so we could learn and make the world better.”

What’s certain is that his oeuvre enjoys a raw, athletic, unpredictable allure lacking in much contemporary art today. As inspired a writer as he was an artist, influenced by the dark, risky, surreal odysseys of authors such as JG Ballard and William Burroughs, he once wrote: “Nothing is more corruptible than truth.” One way or another, then, he was a prophet for our times.

‘Hypothetical Islands’, London, November 5-December 19; ‘Primordial Beginnings’, Paris, November 12-January 9; mariangoodman.com

Comments