How Oxford Street was overrun by sweet shops

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Stretching just over a mile east from Marble Arch, London’s Oxford Street has long been one of the city’s premier shopping destinations. It remains one of Europe’s busiest shopping streets and, as recently as 2018, could command rents of more than £1,000 per square foot, among the most expensive in Europe.

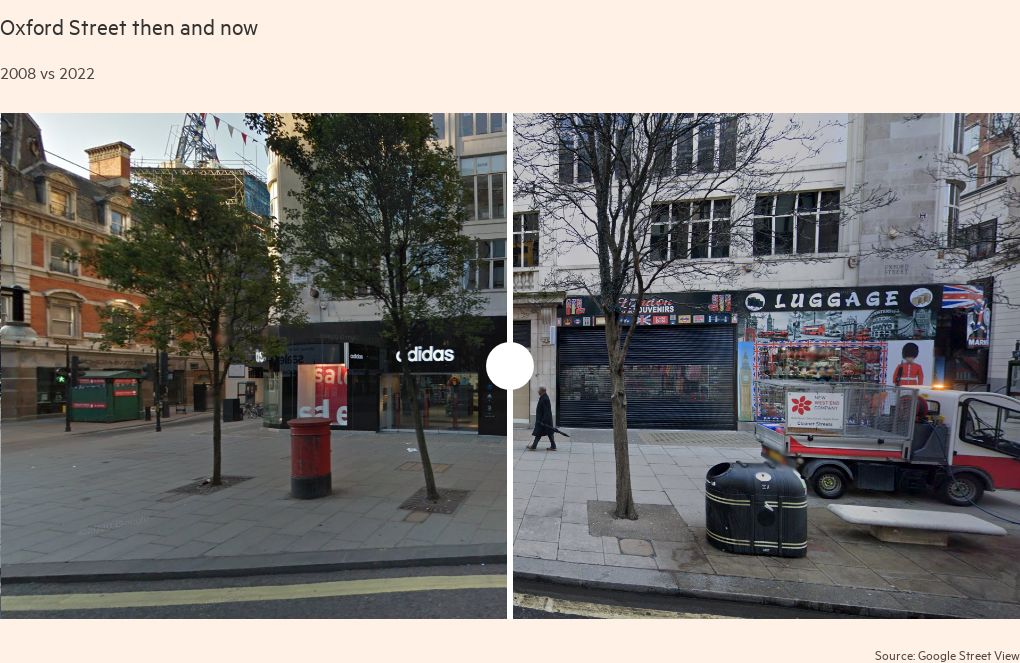

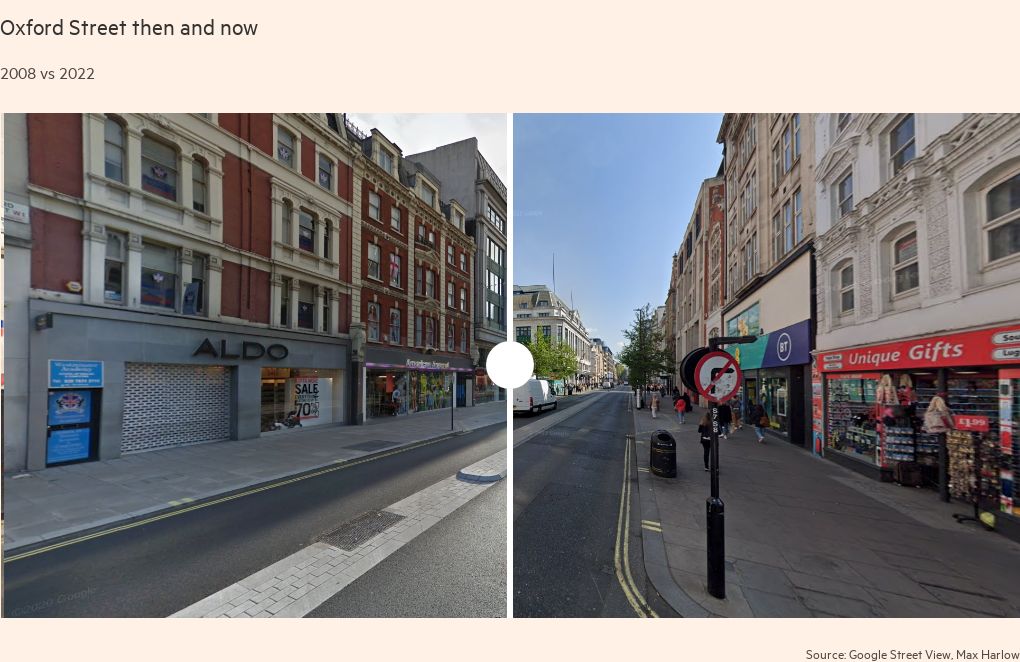

But since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Oxford Street has become barely recognisable. Footfall has declined almost 60 per cent compared with 2019, according to a study by Mytraffic and Cushman & Wakefield. New commercial buildings — comprising tens of thousands of square feet of empty retail space — alternate with tatty souvenir stores and shuttered storefronts.

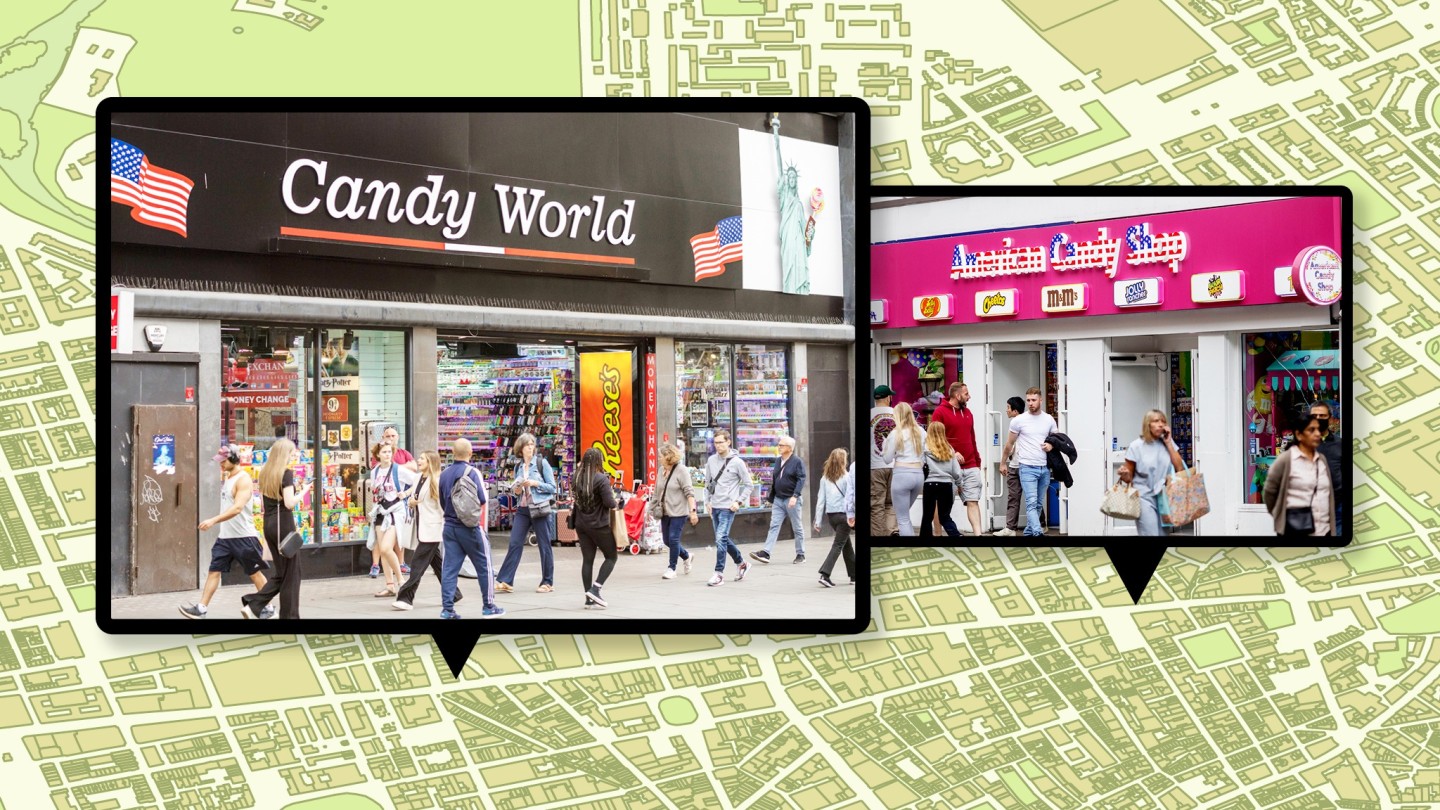

The biggest change has been the rapid influx of brightly lit shops selling colourful American sweets, from Jawbreakers to Jolly Ranchers and Sour Patch Kids. Many have sprung up in place of the high-street retailers that were hard hit by Covid-19 and the shift to online shopping. The number of sweet shops soared during the pandemic. Along with souvenir shops, there are now about 30 of them — the second most common business category on Oxford Street after fashion stores, according to the Local Data Company.

“Oxford Street was de facto Britain’s high street,” says retail consultant Philip Downer. “If I were coming back to Oxford Street for the first time in 10 years I wouldn’t believe my eyes. It’s extraordinary the extent to which this change has been allowed to take place.”

Stuart Machin, chief executive of Marks and Spencer, which is in dispute over plans to rebuild its flagship store on the street, recently said that unless action was taken Oxford Street risked becoming a “dinosaur district destined for extinction”.

As more new shops moved into the street, Westminster City Council, the local authority that collects property tax on the street, realised that the identities of the ultimate occupiers were increasingly hard to track, often hidden in a web of subtenants, agents, intermediaries and shell companies. Many of the businesses are wound up without ever having filed accounts. That has made collecting property taxes almost impossible. In June, the council said it was owed £7.9mn in overdue business rates from 30 sweet and souvenir shops in the area.

The sudden proliferation of sweet shops on a high-end shopping street has perplexed shoppers and tourists — as well as the council. Many landlords and their agents say the changing face of Oxford Street has been fuelled by high business rates. But, for the council, delinquent sweet stores illustrate wider failings in the way the UK deals with fraud and tax evasion — from flaws in how companies are registered, to a disjointed enforcement process that also involves HM Revenue & Customs and insolvency firms.

“It’s a symptom of a deeper structural problem in the economy and society,” says Adam Hug, leader of Westminster Council. “Day in and day out millions of people coming to London see the real world impact of a lack of transparency and accountability.”

Nesting tenants

The job of identifying the occupiers of Oxford Street retail premises, and clawing back unpaid rates, has fallen to Martin Hinckley, head of the Westminster City Council team responsible for business rates. “There’s no requirement in rating law [for landlords] to tell us who’s in there. So it’s up to us to find out,” he says.

That is not as simple as it sounds. Hinckley, 61, says his visits to delinquent premises follow a common pattern. “The [staff] are trained not to give any real information,” he says. “They will say, almost universally, ‘I started today, the manager is not here’. Then they point at a certificate of incorporation. That’s the one company we know in the world isn’t [the operating company].”

The ease with which companies can be created is one problem. Companies House — the corporate registry for England and Wales — has no remit or resources to check information provided to it, which, critics say, makes it easier to mask the ultimate ownership and avoid liability. Companies can incorporate for just £12.

Hinckley suspects a sizeable portion of the directors and shareholders on the paperwork of the companies he has scrutinised are not those in charge. “I’ve seen people being paid to be directors. I wouldn’t trust anything on the shell company. It’s so easy to set up a company and you can put any details that you want,” he adds.

Authorities have long known about such loopholes. After years of delay, the government passed legislation to address some of them in March, as part of an economic crime bill to crack down on dirty money flowing into the UK. A new register requires all owners of overseas companies with control of land in the UK to be identified. Legislation to overhaul Companies House is also expected this year.

Analysis by the Financial Times of companies registered at Oxford Street premises reveals clusters of shareholders and directors who appear to form a loose network, with some sharing residential or business addresses, or taking ownership of a business for months at a time before ceding to another shareholder.

Most have not filed accounts, or were dissolved or put into insolvency before doing so. Some shareholders and directors have gone on to set up new companies on the street or move existing ones to different Oxford Street addresses. One company has been registered at three separate Oxford Street addresses since it was established 10 months ago.

Hinckley’s mission is further complicated by the nesting of tenants, subtenants, agents and intermediaries that makes it difficult to untangle who is liable to pay the rates. Take 474 Oxford Street, adjacent to Marks and Spencer’s flagship outlet and home to a souvenir store called “Ministry of Gifts & Luggage”. A rental advert advises that full rates are set at £340,480 a year, warning prospective tenants to “confirm any rating liability directly with the local authority”.

The freeholder is The Portman Estate and, until last year, the store was occupied by Vodafone, whose lease with Royal London UK Real Estate expires in 2026. In January, the telecoms company sublet the premises to an agent called Maddox Estate, which, according to Vodafone, sublets to third parties — a common practice. Joshua Dehaan, Maddox Estate’s owner, did not respond to questions about the company’s role as an intermediary at a number of premises on Oxford Street.

On a recent visit to the store a man who identified himself as the manager declined to give his name or that of the company that owned the business operating there, but said it paid taxes and business rates. The only company registered at 474 at the time — Western Crown Limited — was owned by a man listed at Companies House as Isfahan Chombo Kade who is also associated with a number of other sweet and souvenir businesses. The manager claimed he did not know Kade. According to Companies House, the company moved from 474 to an address further down Oxford Street shortly after the FT’s visit. Kade did not respond to a request for comment.

In addition to Hinckley’s team at the council, a separate operation in charge of trading standards can carry out inspections to ensure food safety or organise raids to confiscate any suspected counterfeit goods. If there is enough evidence, that team can carry out test purchases to trace payments through the credit card system in the hope of identifying bank accounts and linking companies to them. “It is not always a straight trail where the money’s gone,” says Hinckley.

Early efforts to wind-up delinquent companies in court largely led nowhere as investigators realised most were shells with no assets.

An exception is the “Kingdom of Sweets” business, a brand with a national chain of shops. Two companies linked to it are currently in liquidation after a petition by Westminster council. One of them owed £1.5mn in business rates, according to its administrator’s progress report dated November 2021. The council says “significant amounts” are owed from “companies trading as Kingdom of Sweets”, for which it has “repeatedly demanded payment”. It has begun legal action against two further companies in the group.

A spokesperson for the Kingdom of Sweets business said “we are a respectable business paying all relevant taxes and business rates,” and that steps are in place to pay outstanding rates.

‘Go after every pound’

Unlike neighbouring Regent Street, which is owned by the Crown Estate — the property portfolio owned by the reigning monarch and run as an independent commercial business — Oxford Street’s properties are held by a patchwork of offshore companies, billionaire real estate investors and large landowners such as the Portman and the Grosvenor estates.

Swaths of property along the street have changed hands in the past two decades, fuelled by an influx of Middle Eastern and Asian investors.

Council leader Hug has called on landlords to “take responsibility about who they let [their properties] to”. Some landlords and their agents counter that falling demand has forced them into deals with temporary operators such as the sweet or souvenir shops.

Responsibility for paying the business rates lies with the store’s “occupier”, not necessarily the official tenant, in premises that have been sublet. But when premises are empty the liability falls to landlords, pushing them to heavily discount rents in order to find new tenants. The pandemic was especially painful: retail and hospitality businesses were eligible for rate relief, but landlords’ empty properties were not.

“It appears that the rate system is set up to encourage landlords to make sure that their properties are never empty,” says Robert Hayton, UK president at real estate adviser Altus Group. “If the only choice of a tenant you have is one of these candy stores then, what are you going to do?”

Business rates policy is determined by the government and rates are set according to a formula based on the value of a property. For now, rates are based on significantly higher rental values from 2015. Some of the bigger premises rented to souvenir and sweet shops have annual business rates of £1mn, according to council calculations. Westminster council is the largest collector of business rates in England, taking in about £2.4bn annually in total but most of this is redistributed to local authorities elsewhere around the country.

“The big finger is pointed at government,” says Anthony Selwyn, co-head of the prime global retail team at Savills. “Unless rates change, Oxford Street will recover over a longer period of time than anywhere else.” Others say the council’s focus on sweet stores is misplaced and the real question is why there are so many empty shops on Oxford Street.

Hug agrees that there is a case for business rate reform, but says that does not absolve those evading payment: “We have a duty to go after every pound that we are owed.”

‘Playing whack a mole’

Still, enforcement is a huge challenge. “We are playing whack a mole, trying to tackle the rates evasion,” Hug says. “To go after the root cause we need a cohesive approach between us and central government.”

One area campaigners argue needs attention is enforcement of VAT. One man, who spent decades in the souvenir business, says he first raised the alarm over alleged non-payment of VAT in that trade with HMRC more than a decade ago. He also noted a pattern whereby operators in the sector would wind down companies and transfer their business to another company allegedly in order to evade debt and taxes — a process known as “phoenixing”.

“It would have been such an easy thing to investigate,” says the businessman, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisal. “All the [authorities] had to do was to go in and ask for the receipts and invoices,” he adds. “Of course, word has got around that you can set up a shop and avoid paying VAT and taxes. So other people go into the business as well . . . My business couldn’t compete with people who don’t pay taxes.”

Businesses with an annual turnover of more than £85,000 usually have to register for VAT and companies are responsible for paying it to their suppliers and charging this tax to their customers.

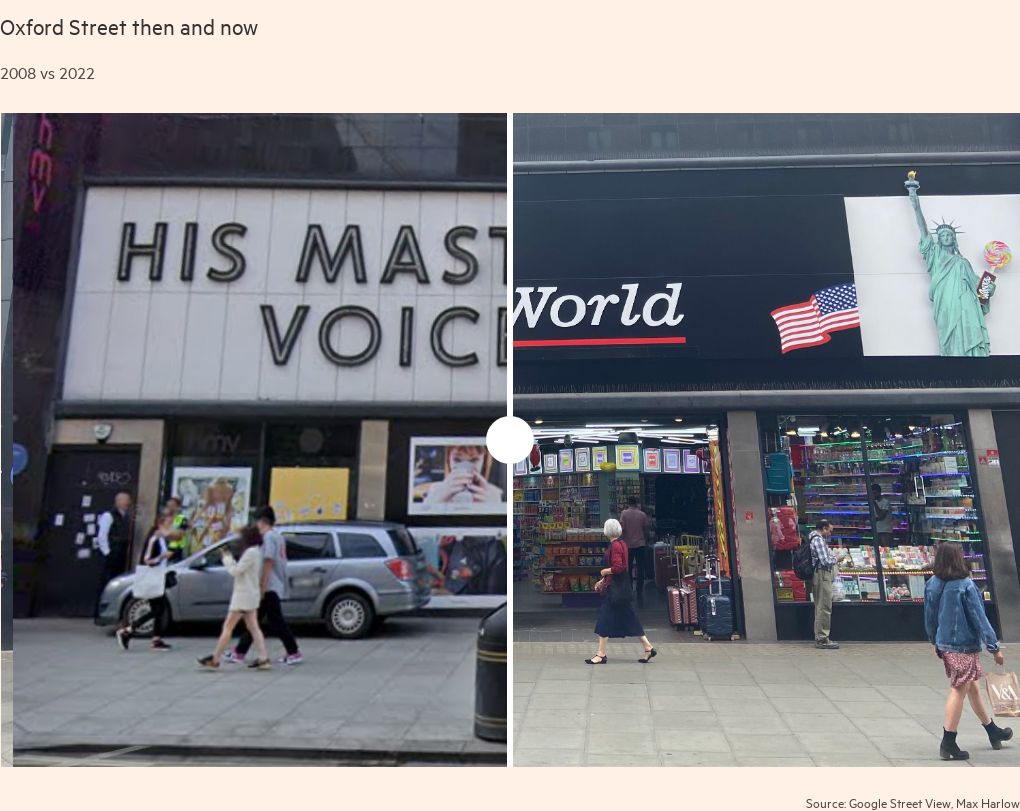

Yet a number of receipts gathered on Oxford Street in July and August by the FT do not seem to include VAT. Among the colourful wares on sale at shop premises branded “Candy World”, for example, a packet of edible paper fashioned into €500 notes and dubbed “Funny Money” costs £1.99, but the receipt lists the VAT rate at 0 per cent rather than the 20 per cent it would normally be on confectionery and some other foodstuffs.

It is unclear which company issued the receipt, as a number of concessions operate at Candy World and the business name printed on the receipt relating to the purchases does not correspond to any active companies registered at 363 Oxford Street, the site of the former His Master’s Voice store. The FT did not receive a response to a letter addressed to concessionaires at 363 Oxford Street asking for comment.

HMRC says the agency cannot comment on identifiable taxpayers, but recognises the “risks associated with contrived insolvencies” as a way to evade tax. HMRC was unable to provide data on whether any directors of sweet or souvenir shops in London have been prosecuted or disqualified.

Yet there are signs that the heyday of candy stores may be over. Some landlords in the street have already served notice on tenants operating such shops. The local area is set for a facelift. More than a dozen buildings are due to be refurbished or rebuilt in coming years.

The New West End Company represents more than 600 retail, hotel and property businesses in central London. It has ambitious redevelopment plans aiming to generate £10bn in annual turnover by 2025 for businesses in the area — an increase of 14 per cent from pre-pandemic levels. Westminster has earmarked £150mn for improvements to the district. It also wants to offer discounted rates to pop-up shops to occupy empty premises, although landlords are sceptical about whether such stores could afford the rent.

“We have to see Oxford Street going through a rebirth,” says Malcolm Cohen of Langham Estates, “[but] it is a difficult rebirth.”

The new Elizabeth Line station at Tottenham Court Road is expected to bring more visitors to the street. Swedish homeware shop Ikea is due to open in 2023, while Selfridges — one of the last remaining department stores on the street — will rework part of its building into a hotel.

Yet opposite Selfridges, the shortcomings of enforcement are visible. At the former site of American Candyland, unopened letters from Companies House lie discarded on the floor. From the window, passers-by can see they are addressed to a Romanian in his 30s — identified via Companies House — whose business has not filed any documents at the registry since it was first established in April 2021.

There is little chance the council will be able to recoup the rates it is owed. But Hinckley recognises the underlying dilemma for the council: “If we were perfect and got rid of them, all we would have is empty shops, which is no better for the street.”

Additional research by Mumena Choudhury

Comments